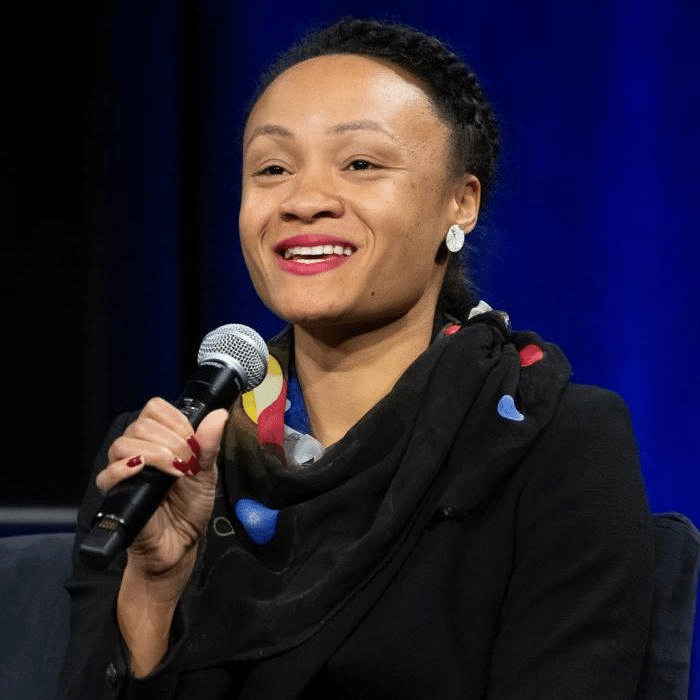

As the Aaron Sorkin global political drama that is 2024 reaches its season finale in the USA today, we are thrilled to share our chat about the politicisation of research with Professor Jenny Reardon, Professor of Sociology at the University of California Santa Cruz, and the Founder of Science and Justice Research Center. Jenny and I met back in June when we both attended a workshop on Science at Social Justice at the Lorenz Center in Leiden, The Netherlands, as a result of a session at Sci Foo 2023 where like-minded people gathered to talk about the state of research and its impact on all of society.

Jenny has a research background in genomics, however she moved into examining the social issues raised by this area of research. In our chat she recalls being optimistic around the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and how this new field of science was a beacon of hope for bringing people of all backgrounds together through commonality. Tempted by the opportunity to combine her love for science, politics and justice, Jenny almost worked on the Human Genome Diversity Project – a project that intended on representing genetic variation across populations. Though the purpose of the project was to showcase how people across the world share fundamental similarities, the project sadly ended up being described as a so-called “vampire project”, sucking the blood of indigenous peoples in the name of research instead of working towards their continued survival.

This project and others like it inspired Jenny to make space for scientists that want to do good in the world without inadvertently contributing to the existing extractive nature of some areas of research, however this is tricky when the entire endeavour of research is more complicated. Current research culture is based on an archaic way of exploring thoughts and ideas, the framework of which was crafted by a fairly homogeneous group of wealthy people who shared similar thoughts and lived experiences hundreds of years ago. These reinforced the informal ways in which power was being distributed across the research profession. What place does that framework hold in today’s research ecosystem? I asked Jenny whether it is time for a research revolution. Naturally she also thinks we should be grabbing our flags and flocking to the barricades. She argues that if we don’t address the politics of research, we are at risk of research being deemed to be an untrustworthy pursuit. She discusses the concept of macropolitics vs micropolitics, reminding us that while we should absolutely be concerned by how the Donald Trump and others will impact research, we should also consider the impact of our own actions have on research culture and whether we are contributing to upholding aspects of a culture that are not conducive to inclusive and impactful research.

Jenny recommends that we stop “othering” the politicisation problem and take a level of individual responsibility and accountability. Most people go into research with idealistic interests, but research is an institution and we must be honest about the fact that, while many research transformations have led to better ways of doing work, there is still a lot to do to unpick the imbalanced power relationships that persist in the scientific method. Reflecting on her own experiences, and resonating with those we have heard from across the research community, Jenny finds it challenging that we don’t equip early career researchers with the tools to navigate the social aspects of the research space. If you are lucky, you may end up in a research group that passes down pearls of wisdom around the bunsen burner, much like our ancestors shared survival tactics around the campfire. However this level of support is not universal, and very much comes down to the luck of the draw. This results in many people feeling that they do not belong in research, and leaving to pursue other paths of interest. Their loss is felt in the absence of their ideas as we innovate to overcome the huge challenges we face as a global society. It also takes a lot of learning, listening and empathy to ensure that the ways we do this are free of racism, colonialism, and other factors that fly in the face of inclusion of all.

Scientists aren’t to blame for this. We work in a culture where very few scientific researchers are trained in social and political issues. If they had a better understanding of these, they have a better chance of doing good in the world through their research. Part of the challenges we need to overcome centres around the value we place on these aspects of research. Much like public engagement and science communication, an awareness of the social and political space is not valued in the same way as other research activities and outputs. By changing the way in which we reward successful research and looking beyond simply publications and grants won to include such skills, we will move another step forward in making research more robust and more inclusive. By changing how we value participation in these activities, we go beyond seeing ethics and the social justice of our research as tick box exercises and move towards understanding how they make the research we conduct better for more groups in society. This is why Jenny and her team focus more on justice than ethics, a term that is now associated with mandatory online courses and workshops that instil fear in researchers instead of empowerment. Justice is about a world where more people are included and their needs and aspirations are being addressed. It is a fundamental facet of the work we do as researchers.

Jenny goes on to talk about how this is a journey that social scientists need to take too. For a long time social science has been presented as a space of purity and neutrality, free of politics, but research is riddled with the politicisation of science, so this is an impossible claim to make and we need to be honest in recognising that, especially as we talk about the differential distribution of power and access to resources. Who is able to ask questions about our world, who can participate in this discourse, and who is really represented? If we continue to present a world in which we claim that research is apolitical, we risk further eroding trust in research.

However we need a massive culture change and global buy-in to move the needle. We need a deeper appreciation for how social issues are impacted by science. Jenny believes that the best research will reflect this more considered way of working. It will be more inclusive, more impactful, and ultimately more trustworthy. Until we change this culture, we aren’t doing the most innovative research as we are simply not making the most of the wealth of ideas out there.

When we talk about science and social justice, conversations about inequitable access to research information spring to mind. However there is also the issue of inequitable access to the production of knowledge too. Red tape and financial hurdles make overcoming these barriers challenging, and working across funding councils based in different continents is almost impossible. How can we solve global challenges when these barriers to impactful collaboration exist? Funding must be available to benefit our entire planet, and not just for the countries from which that funding originates. Overcoming these challenges requires time and resource to build communities and work together to iron out processes that work for everyone. Jenny’s work includes investigating how we can build truly global networks, working out who will fund them, and how we can ensure that funding sources are trusted. She believes that we need a shift in how funders measure their impact and return on investment. Funders need to park their local or national agendas and think bigger and more collaboratively to enable a democratic ethos of how funding is distributed.

So what does this all have to do with politics, and why does the outcome of today’s election matter for research, to the USA and to the world? Where there is politics, there is policy, and this impacts everyone. Policy makers are one tool we have to fundamentally change the culture of how we do research. When we look back at the UK’s own open research journey, the impact of national funding mandates and research assessment exercises have had on the adoption of open science principles. In the USA under the Biden administration, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) created an Office of Science in Society that focuses on the societal impact of research. Headed up by the amazing Alondra Nelson who is trained in science and technology studies and cultural studies, the Office is one way in which policy makers and other stakeholders can think deeply on this issue, and look at research policy through a DEIA lens to determine whether it is truly serving everyone in society, or whether we are still leaving some people out of the discourse.

Whatever the outcome of today’s election, its impact will be felt across the world, from the allocation of funding to the way in which we measure research success and impact. Through Jenny’s work and that of her research centre, while we may have overlooked the inclusion of everyone in the impact of research for a long time, we have an opportunity to take stock and collectively contribute to a more inclusive, trustworthy and impactful research culture.

You can watch the full interview with Jenny on our YouTube channel, and check out our Speaker Series playlist on YouTube which includes chats with some of our previous speakers, as well as our TL;DR Shorts playlist with short, snappy insights from a range of experts on the topics that matter to the research community.

With thanks to Huw James from Science Story Lab for filming and co-producing this interview. Filmed at the Møller Institute, Churchill College at the University of Cambridge in July 2024.