We’re thrilled to be hosting engineer, innovator and the godfather of street skating Rodney Mullen at the Royal Institition in September as part of our Speaker Series Live programme of events. So, to get us in the mood and give us a taste of what to expect, Suze and Huw popped by Rodney’s place while they were out working in Los Angeles to bring you this month’s Speaker Series episode – a conversation about culture, community and creativity in science and skateboarding.

To Rodney, skateboarding was a little like a series of puzzles – in his mind skate tricks were mathematical challenges, ready to be worked out, deconstructed and built back better. Transfers of balance and force and transitions of energy made sense to him, as someone who had honed their interest in and talent for engineering through kits like Erector Sets, in many ways a precursor to Lego. Rodney picked up skateboarding easily and nurtured his natural talent but he knew from an early age that to progress, he would have to think outside the box and “veer off into my own direction”, as he put it. He succeeded and then some, turning pro at the age of 14 and then also going on to use this drive to do things distinctly differently in a career in engineering.

Skateboarding is science, art, athleticism, and innovation borne from a desire to not settle for the status quo. Rodney believes that the spirit of scientists is the same as that of skateboarders – both groups are always asking what they can do to take things in a new direction.

Invention and Innovation

Esther Dyson said in a recent TL;DR Short that as a research community, it is possible that we would benefit from looking back at knowledge that has already been created to see whether it can be further developed, rather than constantly creating new knowledge. Rodney agrees with this, stating that invention only really becomes innovation when it is adopted by the community that benefits from its development. This is true of one of his most well-known skate tricks, the Flat Ground Ollie, a gateway to many other tricks as it allows the board to be lifted into the air so the skater can land on a range of surfaces.

Rodney first performed this trick in 1982 and, although it was received with some interest, it was not until skating started to evolve away from skate parks and pools to the streets that the move was needed, to fully embrace the opportunities to skate in a range of different and novel ways. Rodney says that, like in research, you cannot predict what will have relevance later down the line. We can never know what knowledge that has already been created will come in handy when faced with a new set of future challenges.

This notion of innovation over invention is obvious when we look at the history of skateboarding. The evolution of skateboards – their size, shape, and the composition of their components – has been driven by the needs of the skateboarding community, with flat boards changing to double kicks, for example. This isn’t however for a lack of interest from a range of commercial entities. The recent Skateboard exhibit at the Design Museum showcased how different skating eras were defined by new materials and new designs, but that their development was supported by but not led by chemical and manufacturing companies. Many companies tried to create things that they thought the skate community wanted to further develop the sport, but they didn’t always translate into adoption by the community as these organisations weren’t fully in tune with the community’s needs. Coproduction and cultural understanding were key for commercial success.

One perfect example, and one that Rodney himself has experience working within, is the polyurethane space. Skaters need durable wheels that also possess a fine balance between elasticity and rigidity. Rodney himself says that you can peruse the full catalogue of PU molecules, analyse their bonding, and predict what MIGHT work, but it is only by creating prototypes and having skaters use them that you will know whether you have hit the sweet spot or not. Innovators need to have a feel for the needs of the community they are trying to serve, which is why multiple skill sets are needed in all areas of research and development.

Community Engagement for Innovation

In last week’s TL;DR Short, Courtney Hohne talked about empowering communities to engage in innovation. There are many examples of initiatives that have seen the benefits of creating platforms for engagement to catalyse creativity from the skating community. Rodney cites the Smithsonian’s Innoskate as one example of a programme that nurtures and supports scientific developments from non-traditional scientists. By bringing together a range of lived experiences shaped by different environments and histories, groups of people can better solve problems and most impactfully innovate. Fresh perspectives on existing challenges are good and, just like in research, we need a range of people in the room.

However, we are often constrained by the frameworks within which we measure success. Reflecting on his career in skateboarding, Rodney says that contests can be good, but they can also be constrictive in their nature. There are many parallels with research here. Frameworks for measuring success can help researchers, institutions and other groups and organisations understand how they are progressing, but these frameworks should not stifle productivity and creativity. They also need to be open, flexible and inclusive enough to bring together a range of cultural experiences, to create the most useful and meaningful developments.

Failing to Succeed

Failure needs a rebrand. Referring to skateboarding but also using it as an analogy, Rodney says that the best thing he can teach any new skater is how to fall well. Falling and getting back up again is a skill that needs to be developed, whether on wheels or in a lab. In research, this can mean trying, failing, and trying again to achieve anything from the perfect synthetic method to the ideal characteristics of a material. Rodney believes that learning to fail is freeing, and can unlock a sense of confidence in trying to do things differently.

He feels that this also holds true in business however he argues that failing faster, a method that is so often celebrated in tech, isn’t always the best way to innovate. Failing safely is key – there is a fine line between taking enough of a risk, and not being so irresponsible that you lose it all. Building resilience through failure is a crucial strength to drive more innovation but it is not an experience anyone willingly wants to go through, especially in a world where it is implied that we must succeed in everything we do. Here at Digital Science we ran a ‘#FailTales’ campaign back in 2019 where we encouraged the research community to share their failures, in an attempt to destigmatise this important step in the journey to success. While there was a lot of encouragement and interest, we actually, erm, failed at the campaign, as when push came to shove, very few people were willing to share their own personal stories of failure, for fear of coming across as vulnerable or incompetent. Luckily MIT had better luck with their MIT FAIL! initiative that Rodney was involved with. Whether it is sharing negative results or sharing stories about times things didn’t go to plan, it is important to have an awareness of these things from a research perspective, as we could save so many resources by helping each other out.

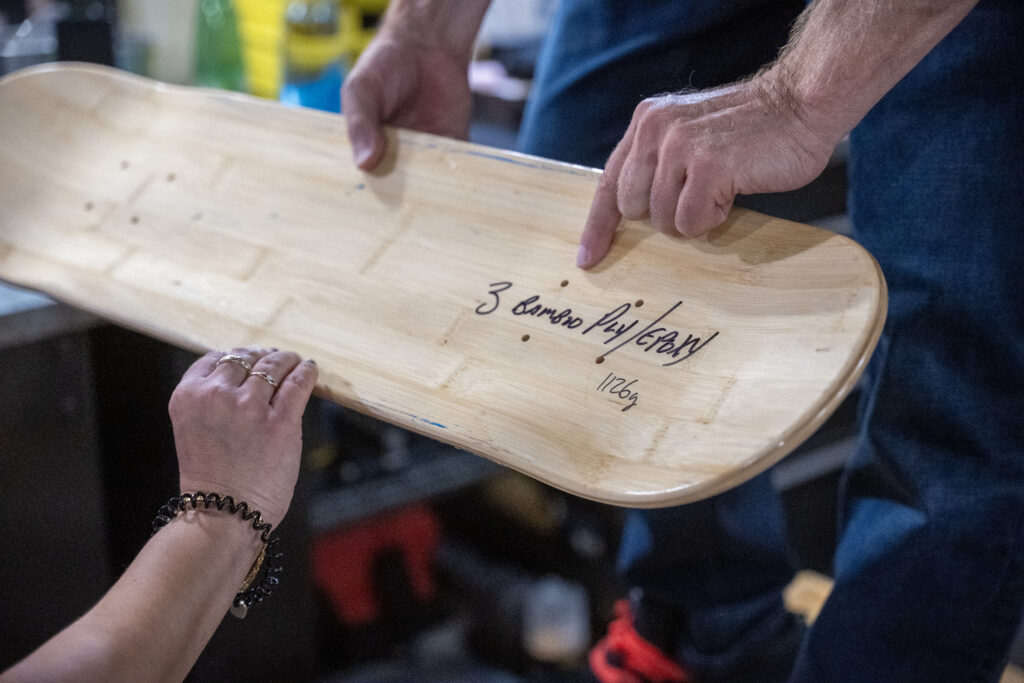

As an engineer, Rodney has created a range of inventions for the skate community. Some of these worked brilliantly and were adopted by the community, but others failed to quite make it off the ground. The community’s loss was my gain, however, as Rodney shared with me some of the material science successes and failures that he has seen as he built a board. It is clear that with his in-depth knowledge of materials chemistry combined with his knowledge of the sport he knows how to create something entirely unique and perfectly tailored to its user – in this case, me. With its magnesium trucks and hollow kingpin, light but strong bamboo deck perfect for variable British weather conditions, and extremely rare bearings, plus a range of other personal touches, the resultant board is not only a thing of beauty, meaning and love, but it is also ideal for a small, keen baby-skater with half-decent balance and terrible ankles that require a good amount of stability. That we were able to take our boards out to test it together was a huge honour. That the board required no tweaks shows what a difference an engineer with lived experience of the object they are creating can make entirely off the fly.

The Future of Skateboarding Science

“All new tech is really old tech”, as Rodney says, but innovative variations on existing inventions are important. Many filed patents are never used, so can we consider this mark of invention as indicative also of innovation and impact? Rodney argues that perhaps rather than making big step changes, we can consider small tweaks to what we already know, as they could lead to many more developments. He would also like to see us taking inspiration from adjacent cultures and communities. As he says, a simple “refactoring of ideas” can explode, creating ripples that reach far into the outskirts of culture, from the music we listen to to the way we dress.

Bringing together a range of experiences allows people to approach problems from new perspectives, and bring fresh approaches to overcoming existing challenges. Rodney hopes that we will not be constrained or limited by metrics of success that can often support homogeneity in the demographics of people included as this can hamper progress, in both skateboarding and in science. He hopes that we continue to work towards a culture and framework that is open and flexible enough to embrace outsiders and create a sense of belonging for a range of people and minds.

Catch Rodney Mullen at the Royal Institition in September as part of our Speaker Series Live programme of events and stay tuned for more science of skateboarding content in the coming weeks.

You can also check out our Speaker Series playlist on YouTube which includes chats with some of our previous speakers, as well as our TL;DR Shorts playlist with short, snappy insights from a range of experts on the topics that matter to the research community.

With thanks to Huw James from Science Story Lab for filming and co-producing this interview. Thanks also to Rodney and Lori for welcoming us into their home in Los Angeles to film this episode.