Soapbox Science is a novel (and very popular!) public outreach platform for promoting women and non-binary scientists and the science they do. Overleaf has been a supporter of Soapbox Science for a number of years — for example in 2017 and in 2019 — and I (John H) was delighted when Isla reached out to us about their 2023 event, being held on London’s Southbank on the 27th May 2023.

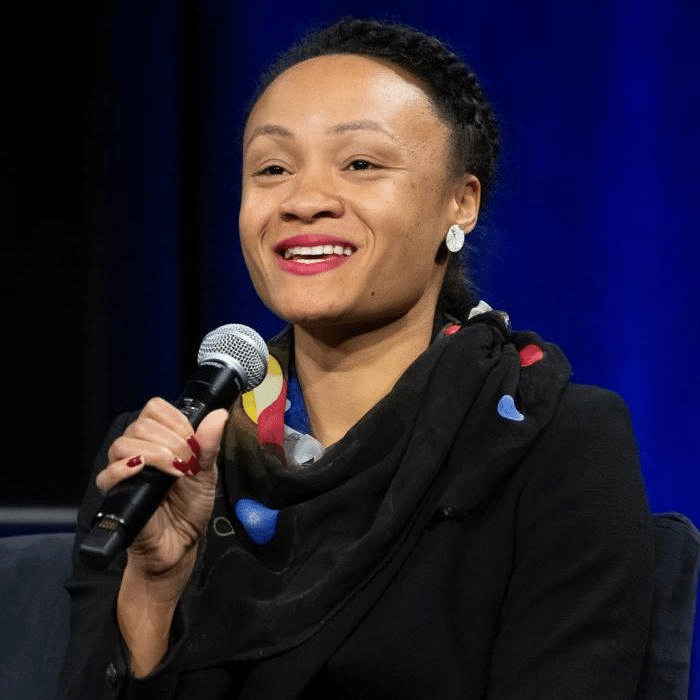

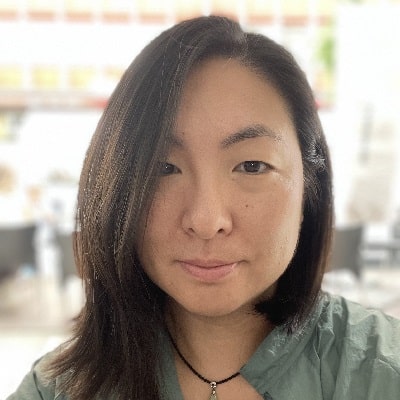

Ahead of the event, we caught up with both Isla, who is responsible for recruiting and training Soapbox Science Local Organising Teams and supporting the delivery of Soapbox Science events globally, and Hui Gong, a neuroscientist at The Francis Crick Institute and one of the London speakers for Soapbox Science 2023! Here’s what we covered in our hour-long chat!

PS: If you only have time to read one section, you should definitely check out what happened when Suze asked Hui a question about fruit flies! 😂

Quick links

- Update: A successful day in the sun!

- How Soapbox Science got started

- Studying flies and their brains

- Location, location, location!

- Capturing the public’s imagination – especially the kids!

- Empowering the speakers

- Breaking down barriers

- The value of public engagement in research

- Getting hands on

- Keeping it simple

- Soapbox Science around the globe

- Be careful if you ask a question about fruit flies! 😅

- Diversity, engagement, and reaching new people

- The importance of social media

Update: A successful day in the sun!

A quick update from Isla!

The day went really well and we were super lucky with the weather. We had lots of great feedback and there was a little girl and her mum who stayed for the full three hours (and watched the shark talk twice through).

“Hui and her fruit flies were an absolute hit with the kids!”

Isla Watton, Soapbox Science Coordinator

Soapbox Science Co-founder Prof. Nathalie Pettorelli also shared some photos from the day:

Read on to find out how Soapbox Science got started, and take a look at the @SoapboxScience account on Twitter for more photos and videos from the events held annually, all around the world!

How Soapbox Science got started

John Hammersley: To kick things off, could you tell us a bit about the origins of Soapbox Science: how it came about, how you got involved, and how this year’s event is shaping up?

Isla Watton:

Soapbox Science started back in 2011 — which feels like a long time ago now! It was started by Prof. Nathalie Pettorelli and Prof. Seirian Sumner, both research biologists who each won a L’Oreal For Women in Science Award and then got connected to each other. With Soapbox Science, they’ve essentially brought their two loves together: Nathalie is really involved with diversity in science, and Seirian’s really into outreach and public engagement. So they decided to combine the two into an event that happens on the street, showcases women and non-binary people in science, and aims to reach people that wouldn’t usually choose to go to a science event — at least 50% of the audience are people that just happened to walk past the space, and then stumbled across some science that day!

So it started with one event in London, and since then it’s grown to…I think we’ve got 35 events around the world this year. These are different teams who’ve reached out to us and said, “Oh, we love this” or maybe it was past speakers who decided that they wanted to have an event in their city. And then they organise their own teams, and we train them in how to deliver those events.

The London event is still going strong in its 13th year now, and we’re still in the same place on the South Bank, which is great because we get great footfall there. We feature speakers from different institutions around London — this year we’ve got 12 speakers who are going to come and give a talk for an hour on the day. So we’re really excited about that!

Studying flies and their brains

John Hammersley: Which nicely brings us onto the speaker that we have on the call today — Hui Gong! Hui, could you tell us a bit about your research, what your talk’s about, and how/why you got involved with Soapbox Science?

Hui Gong:

So first of all my research: I’m a neuroscientist but specifically I study flies and their brains. The specific type of flies are called fruit flies — Drosophila melanogaster — and what we do in our lab is we compare brains of different species of flies to find what’s different and how it has evolved. Our work is based on the olfactory system — the one that does the sense of smell — and what has changed in those neurons and how they function across different species.

What I want to talk about in the actual Soapbox Science event is slightly simpler. I have a few ideas I’m thinking of covering.

One is that I don’t think that many people think about insects and especially larvae, or maggots, having brains. So I think it’ll be interesting to tell the public about how even maggots have very functional brains, and they even have olfactory preferences, so they prefer some odours above others. And that can be different in different species of flies. And I think that’s quite interesting!

To make this more tangible, we have a number of 3D models of insect brains (inc. the brain of the Drosophila melanogaster adult) and we were thinking of 3D printing them in the lab, along with a human brain, to pass them around as props for people to compare how different, or how similar, they look! A human brain and fly brain are quite dissimilar, but if you were a neuroscientist, you might be able to spot some similarities across them 🙂

I was also thinking of including the sense of smell into the activity, but I haven’t really thought about exactly what I’m going to do there yet!

And to answer your last question, the reason I wanted to do this Soapbox Science event is because I’ve always been interested in public engagement, and trying to encourage as many people — in particular as many children and younger kids as possible — to get into science, because as a kid I was really into science but I lived in a very small place without these types of opportunities to see and meet real scientists..

I think it would be great to provide the opportunity to other people, to have this experience — I would have loved to have this experience when I was younger! And a personal motivation is to get better at public speaking, to get over the fear of having to speak in front of strangers outside on the street. I think it will greatly improve my confidence when I have to present my work in an academic environment as well!

Location, location, location!

John Hammersley: Standing on a soapbox speaking in public fills me with dread! Even though I’ve given a fair number of talks, they’ve always been in a room with an audience who would already have some interest in what I was going to say (I hope!). Speaking to the public feels a lot scarier!

Suze Kundu: Training through doing (by participating in Soapbox Science) is also so important because it’s not just you on your own — Isla, you have these cohorts of scientists that do it each time. And there’s something quite purposeful about how you have chosen to do this, because if you can stand in a public place and engage with people of all ages, of all interest levels, it’s a very rewarding way to practice speaking. It’s also a baptism by fire because if you can do that, you can probably engage with anyone at any opportunity! So I think it’s just fantastic.

I am curious about your locations as well. You talked about being on the South Bank as an example in London. It’s predominantly an arty place — you have museums and galleries there, along with bars and other cultural institutions. So do you choose your place quite purposefully where you feel that there are people that could be switched on and engaged in culture, but may not necessarily have had the exposure to science? How do you choose your locations?

Isla Watton:

So how we pitch it to the local teams when they’re picking a space is basically:

- pick somewhere with high footfall because it is scary to stand on a soapbox and be worried about people coming over. So you want somewhere where there is lots of crowd movement, where people are interested;

- pick somewhere where people want to spend a little bit of time. So somewhere like the South Bank is great because people are there to relax and have a leisurely stroll, whereas if you pick somewhere that’s by the entrance to a tube station, yeah you’re going to have loads of footfall, but people are just going to rush past you;

- and the final thing is to pick somewhere that’s not a science space. So yeah you’re right — on the South Bank there’s a lot of cultural institutions, it’s right by Gabriel’s Wharf which has loads of street food. So people come there for a nice day out with the family, and there’s always stuff going on, but it’s not where all of the museums are located like the Science Museum.

From our questionnaires that we do in the evaluation, about 40% of people say that they rarely or never attend science events, which is quite a high proportion for us and it’s really nice to then hear those people say “Oh yeah, this was really fun and I’d love to do something like this again.” It’s moments like these that remind you how worthwhile the event is!

Suze Kundu: I love that positive association of “a good day out”, because science is exciting, and catching people in a place where they perhaps weren’t expecting it, and so might be more open to it… I think it’s really lovely.

Capturing the public’s imagination – especially the kids!

“It’s okay. I’ve got it from here…”

a little girl (a.k.a. a future scientist!) at Soapbox Science in Cardiff

John Hammersley: Do you have any memorable memories from a particular Soapbox Science event that really stand out? Say something that really caught people’s imaginations?

Isla Watton:

Well I’ve been to quite a few of the events over the years — I started in 2016 and so it’s been a while now! But the first one that comes to mind is when I went to an event in Cardiff and one of the speakers was giving a talk about microbes. There was this little girl there who was just really into it… and the way that the talks work is that there are four speakers at a time, each on their boxes for an hour, with the audience free to move between them. They each repeat a 10 to 15-minute talk several times as new people come over.

So this little girl stood in front of the scientist and watched her talk three times all the way through, and then when she was about to start it for the fourth time, the little girl says “It’s okay. I’ve got it from here” and decided she was going to give the talk! So they gave it together 🥹

It was just really sweet to see – just a tiny girl that comes along, is so into the talk — which was actually quite an in-depth topic on microbes — and then decides “this is for me, I actually feel empowered to give this talk myself now, to the crowd”.

John Hammersley: Oh wow, that is brilliant!

Suze Kundu: I love that so much and you talk a lot about impact and evaluation and that is such an obvious impact to have; it could be that that child has never met a woman or a nonbinary person that also identifies as a scientist, because we do have still a lot of these stereotypes that build up even in young kids. I remember there are some studies saying that the perceptions of gendered roles and society come in at such an early age, and as much as you try and work against them, they get in through school, through other friends, and in their family networks. So it is this real opportunity to showcase real scientists.

Empowering the speakers

Suze Kundu: On the impact theme, what kinds of tangible changes have you seen from these activities in the time that you’ve been working at Soapbox Science or in the 12-13 years that it’s been running?

Isla Watton:

We do evaluation on the day with the public that comes by, and it’s really nice to see people who don’t normally engage with science come away saying it was great. And we love to hear the anecdotal things, like you said, people that haven’t seen a woman in science before or even maybe just spoken to a scientist at all and this is their first experience of that. I think it’s really important they take that away, and then next time they think about say physics or physicists, the first image in their mind is that really cool person that they saw who just happened to be a woman or a non-binary person and they were a physicist.

We don’t do any kind of long-term studies with our audience because we don’t collect personal details, but we do evaluate the impact on speakers. They find that Soapbox Science really does help with their public speaking and their confidence at work, and in networking, which is really nice to see. They often have this idea that people won’t be interested in their work, or that what they do in the lab is somehow boring, but when they take it out to the public and people love it, it gives the speaker a huge confidence boost!

Some of the speakers have even said they’ve changed the focus of their research, depending on what people have been really interested in, and it’s taken them in different directions. So I think the impact on speakers is something that we’ve seen for a long time. A lot of our speakers have been inspired to set up their own events or get involved in other areas of public engagement — they come away feeling “Oh, actually, this is a career for me and it’s really important.”

Breaking down barriers

Isla Watton: In terms of the change over the years, even in 2016 when I started we were still getting negative comments from people in the street. There was one event where a girl was really interested and then the mum came over and said, “Oh, that’s science, that’s not for you.”

“Oh, that’s science, that’s not for you.”

mother to her curious young daughter 😢

It’s shocking when you hear that because you live in your little bubble of thinking “Oh, obviously anyone can do anything and I know loads of women who work in science”, and to then see those opinions and stereotypes on the street is really quite jarring. Thankfully, in the past few years there’s been a lot more work in schools and a lot more public engagement projects like Pint of Science, Skype a Scientist, and work from the British Science Association, they’re all doing great stuff and I think there is a bit more of an awareness that who’s giving the message of science is important. Which is great — so we want more of that progress!

Suze Kundu: And I suppose maybe there’s a real opportunity here then because as you say, all of these different organizations are creating programs of engagement, but they are often by age group or particular interest. Whereas with Soapbox Science you have that opportunity to engage multi-generational families and households. So if you’re then changing the perception of the parents as well as the children, hopefully we’ll see less of the “Well that’s not for you” reaction and maybe a little bit more of that “Well we’ve both found that really interesting. So let’s explore this more.” So I think that’s just brilliant.

The value of public engagement in research

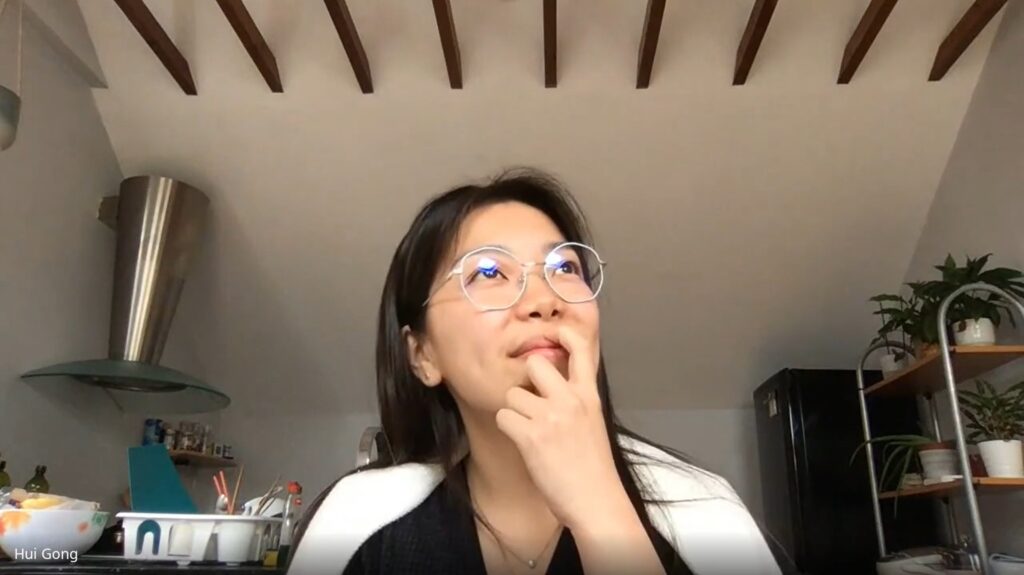

Suze Kundu: Hui – there’s been maybe a bit of an overlooking of the value of public engagement in research, but as Isla has said, here is a real opportunity to make your research better through speaking to and hearing the reaction of the public. So do you think that public engagement is changing? Do you think that the value of it is being better understood in research these days? And do you feel supported in doing this alongside your work — is it incorporated into part of your responsibility as a researcher?

Hui Gong:

From the time that I’ve started doing my PhD, I’ve definitely seen more and more effort put into public engagement in my workplace in the Francis Crick Institute. We have a public engagement team, and downstairs there’s now always an exhibition about something science related. For example, I think we are currently hosting an exhibition on genetic modifications, the “Cut and Paste” exhibition, which is open to the public.

The institute also periodically runs a “meet a scientist” event, for families to come in and just talk to scientists, and there’s a public engagement day (Discovery Day) once a year which is aimed at families as well. Everyone has a little stall and you can pitch an activity that is either related to your science or something you want to do. In the past we have shown some neuroscience related to optical illusions, and also how to control a video game solely using your muscles (your muscle action potential). You put on a patch which uses the electricity going through your body to control the video game!

I’ve also been hearing more about public engagement. What influenced me was the Science Museum. The first time I came to London for an interview at Imperial I went to the Science Museum, and since then I’ve been going back (and back and back) for the Science Museum Lates. I meet so many interesting people there, and many people also say they’re doing public engagement, and I think that also inspires me. I don’t know if I’m biased though!

Suze Kundu: I love that! We’ve probably danced together at a silent disco at the Science Museum, then.

Hui Gong: Probably!

Getting hands on

John Hammersley: One of the other points you’ve both mentioned a few times now is how Soapbox Science is showing people hands-on science, rather than it being recorded or streamed out. How important is that to you?

Isla Watton:

Yes, it’s very much an in-person event, for the people who are there at the time, because it’s not so much a talk but a two-way conversation with the audience.

When we do our training with speakers — and Hui, you did this last week — we give tips on how to build in that conversation, how to get the audience involved right from the start, so they feel that this is a dialogue and that the speaker really does want their feedback on what they’re saying. Kids are great for this — they’re always the first ones to get involved! Even if it’s just a kid who constantly has their hand up with “I have a fact about a shark as well.”, it breaks the ice!

And then separately to Soapbox Science there are already some really good projects that already do recorded talks that people can see at home and I think it’s important that we all work together and offer a different, complementary thing. So for us it’s more about reaching those people who happen to be there on the day and making them feel like they’re special and this is a personal experience for them.

Keeping it simple

John Hammersley: Hui, when you were talking earlier you made the point that to prepare for the talk you had to take a step back a little bit and simplify things, focusing on questions like “does a maggot have a brain?“, rather than diving into the details of your research. It’s quite a skill to be able to take that kind of step back, does that come naturally to you, or have you had training in how to prepare for talks?

Hui Gong:

Well, it’s funny you should mention that, as the latest training I got was from Isla! She emphasised that it’s important to distil down your science into one or two key messages and then work backwards from there. And also from the past, when giving scientific talks to an audience that is not in your niche field, you already have to look a little bit from the outside perspective and figure out how to make your talk as easily understandable to—and as easily followed by—audiences that might not have heard anything about e.g. the olfactory system of Drosophila flies.

So every time that you give a talk, you have to think about your audience, who you’re talking to, what content is appropriate, and at what level you want to speak at. For giving public engagement talks, you focus at an even higher level, and have to think about “What’s the most important thing or most interesting thing about your research that you could communicate to your audience?”

But it’s been step-by-step, little by little that I got here!

Suze Kundu: It’s such a valuable skill to have! This has always been something that we’ve noticed — I’ve trained researchers to do public engagement talks in the past, and my husband still does it, and there is always that moment when people realise “Oh my gosh, this is actually impacting my comms so much more broadly than I thought it would!”. And here you’re inviting that two-way conversation, that dialogue, which is just great.

Soapbox Science around the globe

Suze Kundu: So I guess maybe building on that: you’ve talked about how Soapbox Science is spreading across lots of different countries, including non-English speaking countries as well. In the world of academia, research papers tend to be published in English only, and that can often be a barrier to inclusion and to engagement. Do you see any effects of this language barrier or a difference in people’s perceptions or interest levels in the different countries?

Isla Watton:

We do indeed have events in non-English speaking countries, and they do the events in the predominant language or languages of those places. But it doesn’t seem related to popularity — we do see some countries where there’s loads of appetite for it, and others where there’s not. For example, we’ve struggled to find a team that wants to do it in France (I’m not sure why! Any volunteers for next year please get in touch!), whereas in Germany it’s just totally taken off and we’ve got events in multiple cities there, they’re just so keen for it! But I would just be speculating if I tried to come up with a reason why!

Another great example is Brazil — they’re so keen on Soapbox Science, and from things that the organisers and speakers have said, with all of the political things that have been happening over the past few years, the voice of scientists is really important to the public there and it was important for the researchers to build a community with each other. So it was really nice for us to be able to just offer them the training and they then took it from there.

We have to do the events in the language of the people that are going to visit because they’re who we’re reaching out to, and it’s not a scientific audience, so it’s really important to have speakers who can speak the native language. They’re also all local to institutions there, and that’s one thing about the event that’s also really nice is that people get to see people who are working in their city on science and think “actually our city is amazing, and there are great scientists that are doing work right here that’s impacting knowledge in the whole world”. That’s always really nice to see.

Suze Kundu: I love that there is the aspect of local culture and community building as well. You said it yourself, it’s so valuable engaging people with what’s going on in their local city. Brazil’s a really interesting one, and it kind of doesn’t surprise me that they’re so keen on these engagement opportunities. I think in some of the work that we’ve done here before we’ve noticed that countries like Brazil are really leading the way in pushing for better ways of doing research — their uptake of open science tools and practices is often ahead of so many other countries. So it’s great to see they’ve picked up on Soapbox Science and are running with it!

Be careful if you ask a question about fruit flies! 😅

Suze Kundu: May I ask a question about fruit flies? The mention of Drosophila just takes me straight back to biology class in school. You know, we were talking about the benefit of hands-on science and not of a pre-prescribed experiment because in school, they’re so often really demos rather than experiments because we know what’s going to happen. But the Drosophila experiments that I remember from school really felt like one of the first times that we were doing real science because we were looking at, I think it was eye colour or something, or the colour of their tummies, to work out the genetics of Drosophila.

So for something so tiny they’re pretty mighty. What’s your favourite fact about Drosophila? Hit me with the most interesting thing about fruit flies.

Hui Gong: You put me on the spot here! Hmm, I have one but I don’t know whether it’s super appropriate. It’s the first one that came to mind…

Suze Kundu: Do it… do it, do it, do it…

Hui Gong: So, the first is that how you identify different species of flies is by looking at the shape of the genitals of the male. But…connected to that, the brain of a maggot… well let’s just say that how it looks is a very phallic shape! It’s basically two lobes, the brain lobes, and then there’s the ventral nerve cord, which is basically the spinal cord of the larva. And that just makes it look very, very similar to the male human anatomy part.

Suze Kundu: Wow…

Hui Gong: I was first thinking of maybe 3D printing those, but then I thought it’s probably not very appropriate. So I’m just gonna stick to the adult brain which looks very, very different.

Suze Kundu: Oh my God.

John Hammersley: That is a brilliant fact. I had no idea… I definitely learned something today.

Suze Kundu: It’s one of those things where, you know, if you’re really in the weeds with something and you’re thinking, “this is great, I’m going to 3D print this thing”, just having that outside voice going “Oh, hang on a minute. Oh, hang on. I know people and I know how this is gonna go”.

Hui Gong: Exactly. Exactly. I still remember because we were three PhD students starting at the same time, and the person that taught us how to dissect the brains out was telling us, don’t laugh. Look at this, but don’t laugh. We were wondering why… and then she just drew two circles and then a little bit of a shaft and then we were like, “okay now we get it!”.

Suze Kundu: It’s brilliant. I remember, I used to co-organise a science cabaret night for adults in a pub, but adults and five-year-old primary school kids are not very different when it comes to public engagement stuff, and we were doing these long exposure photography things with LED lights and we were getting people to write their favourite elements in the air as we did this long exposure shot.

And of course, if people have an opportunity to graffiti, it’s always going to be your “maggot brains” that they go to. We got these beautiful photos back… and we had to say that there were these “cactuses” in the background because we couldn’t explain why on Earth there were these strange shapes. But yeah, if there’s an opportunity, then they’ll always be one somewhere.

Hui Gong: Yeah. We’re all kids in the end!

<knock knock joke cut from the article — if you read this far, ping John H on Twitter to hear it 🙂 >

Diversity, engagement, and reaching new people

John Hammersley: You mentioned 35 sites for the events this year — I guess COVID had a big impact in the sense that you couldn’t do in-person events for a while. But it seems to come back strongly since then. Are you seeing it grow a lot? Are you expecting to do more next year as well? What’s the future of Soapbox Science?

Isla Watton:

Yeah, hopefully we will continue to grow! We tend to grow every year with new events teams saying they want to come and do one — we’ve got our first event in Spain this year, which is great. And some new events in Canada, and Australia, and Germany, which is really nice. We did have an impact obviously with Covid in that we couldn’t run live events, but in some ways it was simple in that we just paused the programme — like I said earlier, there’s a lot of really great programmes that are doing online engagement, so it’s not really a space we were going to pivot into.

Coming back after the pandemic, last year was our first year back, and it just felt so nice to come back and actually do it in person again, especially because there was maybe more of an appetite for it. During the pandemic there was—in the UK at least—a disconnect between the science being done about vaccine research and COVID, which was pretty evenly split between men and women scientists, and then the people they chose to present that science and talk to in the media, which was mostly men. So again, there’s this kind of divide of who was actually giving the message, and I think a lot of people working in science felt that and wanted to come back out and actually show that “we’re here and we’re doing science, and science is cool and you can trust science. And we’re real people like you who are doing it”.

It’s taken a little bit of time to build back up after COVID — our teams are all run by volunteers, they’re mostly academics who work in the cities where they’re putting on the events. All of our speakers are full-time academics, and I think there’s been a lot of pressure on people in the last few years with working from home and with new ways of working, and family commitments. So it’s taken a little bit of time to work back up, but we’re back to where we were before COVID and hopefully there’ll continue to be an appetite for it and we’ll continue to grow. New people come to us every year and say they want to organise an event, so hopefully, we’ve got some exciting stuff on the horizon!

John Hammersley: No, it’s great. Like you say, in a way it’s simpler just to say “Okay, we can’t do this during the pandemic. We’ll wait until we can do it again rather than trying to figure out a way to do it virtually”. The government’s messaging of science, the spokespeople that they choose — I agree, look how critical that is in people’s perception of science. Because a lot of people’s view on science is what they see through the news. But it does feel like there is a growing desire to showcase the diversity of people in science.

The importance of social media

John Hammersley: Social media platforms like Twitter, whilst not perfect by any means, do enable the public to get a bit closer to the actual scientist now than previously, when you’d only be able to read an article in a magazine or see science on the news. Now you can hear directly, personally from the scientists themselves. Do you think that’s having a positive impact? What are your thoughts on social media?

Isla Watton:

I do think social media is really important and yes, currently there are some issues with Twitter, but aside from that I think it’s really good. There are a lot of scientists who have built up a really big following that they never would have had beforehand, who’ve got opportunities through that and managed to network with people who work in different cities but work on the same thing. I’m not a scientist myself but I’ve spoken to colleagues and people who go to conferences who say “Oh this is a person I met through Twitter”, and that’s kind of been the introduction beforehand. I think it’s really good to connect people together in that way.

They’re also giving out information in a more informal way, because when you share information through an article in the newspaper, or you get interviewed on the radio or on TV, it usually feels very formal, whereas on social media you can just answer a quick question from someone. Even if it feels silly, even if it’s something like “Does the animal that you study fart?”, you can give that answer and people get excited about science again because you’re answering the things that they actually really want to know!

Suze Kundu: Yeah, definitely. The sentiment about Twitter being a place for community building, breaking down barriers and building a profile for yourself — we actually wrote something about this recently that echoes a lot of what you just said, and your experiences as well. But I also think the thing you mentioned about trust was really important. This is maybe one of those opportunities where you can really humanise the scientists and in doing so, break down that sort of “them and us” idea, instead, you start to think “Well actually they are just like me, and their motivations are really noble and they’re trying to do good things”, and you then start to build trust and the understanding that everybody’s striving for the same thing.

Hui, do you feel that with your research as well? Do you find that you’re working in an environment/field that encourages public engagement, and if so, does that cause it to snowball a bit? Once you start doing something well (e.g. public engagement), you’re often the person who’s then asked to do all the things related to that — is that a privilege? Is that a challenge? Do you think everybody should get involved in this?

Hui Gong:

I think our community is pretty good for this, and how I got more hands-on with public engagement within the Crick was thanks to some of my other colleagues in neuroscience — they wanted to do an activity for one of the public education days, and they were asking for volunteers…and so I volunteered. And then the next year I was on it as well. And so on and so forth.

I kept telling my other colleagues from my own lab “Oh, maybe we should do this and that”, and last year they got involved in public engagement as well, and so I think it did snowball a little bit! So hopefully it will just keep spreading and spreading and spreading!

I also wanted to add a note on the social media question, because not only Twitter, I see more and more people using Instagram. There are loads of actual scientists, slightly on the younger side, like PhD students or something like that, and they’re just portraying themselves going through their daily lives. Often with a comedic context as well, or showing what they do in the lab. And I think that just makes scientists very relatable to normal people! 🙂

As you said, we’re just people, we have the same motivations, we do the same stuff and we find the same things funny, and I think that type of engagement can reach a lot of the younger audience as well. Just like I’m hoping to do at Soapbox Science!

Suze Kundu: What a great note to end on! Hui, Isla, it’s been brilliant speaking to you today, and we wish you both the best of luck for Saturday!

To find out more about Soapbox Science 2023, head to their website! Or to read more interviews from John and Suze, check out the community section of TL;DR.