When considering research transformation within the research ecosystem, it is hard to think of a greater change than the rise of persistent identifiers (DOIs and ORCiDs being two prominent examples.) Arising out of the original digital transformation of research in the internet age, persistent identifiers emerged out of the need to refer to the same digital object over time, even though every single piece of infrastructure used to support it might change.

From a narrow perspective persistent identifiers (PIDs) might be understood as a response to a technical problem, however the key innovation surrounding persistent identifiers has been an ever- expanding social infrastructure – a constant invitation to collaborate, with roots that stretch much further back than the internet.

It begins in 1973…

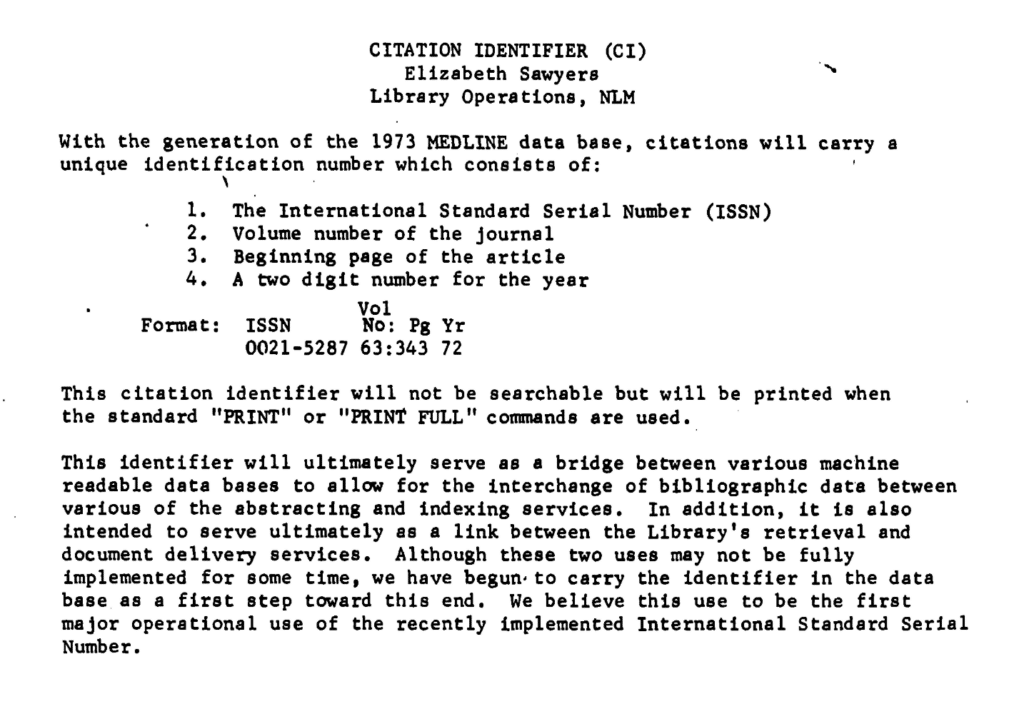

Although you might think of persistent identifiers as something particularly linked to the digital age, I think a useful starting point is to consider the creation of perhaps the first citation identifier in 1973. Within a National Library of Medicine (NLM) document from 1972 is the following note:

“With the generation of the 1973 MEDLINE database, citations will carry a unique identification number which consists of:

- The International Standard Serial Number (ISSN)

- Volume number of the journal

- Beginning page of the article

- A two digit number for the year…

…This identifier will ultimately serve as a bridge between various machine readable data bases to allow for the interchange of bibliographic data between various of the abstracting and indexing services. In addition, it is also intended to serve ultimately as a link between the Library’s retrieval and document delivery services. Although these two uses may not be fully implemented for some time, we have begun to carry the identifier in the database as a first step toward this end. We believe this use to be the first major operational use of the recently implemented International Standard Serial Number.”

Within this short statement are some of the key ideas behind the persistent identifiers that we use today. Not only does the identifier point to something, it is an open bridge between different knowledge sets – an invitation to connect. Reading further, we see that this identifier is built upon the fruits of a significant international collaboration between publishers and libraries. The newly created ISSN – established to identify journals as they transform through time – provides a language to identify the same research articles across different databases and representations. By becoming the first major adopter of the recently implemented ISSN, the NLM also exhibits another common feature of the persistent identifier story – the capacity to invest and place trust in the future success of community-developed infrastructure.

While the implementation of the first citation identifier was short-lived (it seems to be deleted from MEDLINE files by 1979), the service in which it was embodied was certainly not. The MEDLINE index, now most prominently accessed through PubMed, and syndicated through almost every other comprehensive research search index, is today an essential part of any medical researcher’s toolkit, and the use of PubMed IDs to refer to publications is commonplace.

2002: From catalogue to community….

With the arrival of the internet in 1995 and the move towards digital rather than physical, the need for a persistent identifier had resurfaced, this time to solve the problem of being able to persistently locate the digital representation of an article, as websites, digital infrastructure and even publisher ownership changed around them.

Unlike the citation identifier proposed in 1973, the implementation of Digital Object Identifiers in 2002 would do more than just bridge representations together. Instead, facilitated by Crossref, and scaffolded by emerging common understanding of how to digitally describe a research article (JATS-XML), DOIs for research articles would encapsulate a representation of the object that they describe, along with a persistable link to where you could find it. More than just a technology, facilitated by CrossRef, DOIs effectively shift responsibility for journal article metadata from citation indexes back to publishers. This responsibility extends to not just assigning DOIs to their research articles, but also to using DOIs to reference other articles. To put it another way, DOIs are made real through shared meaning and practice within the publishing community.

Although initiated within and between publishers, DOIs provided other invitations to collaborate within the broader research community. Current Research Information Systems (such as Symplectic Elements) could enable institutions to choose which representation of a publication they wanted to include in their system. Common identifiers provided institutions with a choice over the publication data providers that they consume. Institutions are able to create their own representation of publications - enhanced with links to university staff and local research classifications, and yet linked by a DOI, able to connect this representation to a broader ecosystem of metrics offered by an expanding set of service providers.

Over the next two decades, outside of publications, the use of DOIs in Wikipedia, policy documents, Twitter/X, Facebook etc., creates new invitations and possibilities for services that track alternative metrics (such as Altmetric)

2009: From publications to datasets…

From the perspective of 2024 the idea that you should also be able to cite datasets as well as publications seems natural, however this is the result of concerted efforts to transform research practice over the last 20 years. Finding a growing network of support in 2009, the initiative is not led by publishers this time, but instead by the library community. Although data repositories had already existed within institutions with local identifiers, the idea of of a DOI for datasets brings with it an associated set of expectations - datasets should be able to accumulate metrics, we should be able to assess their impact on research, and as with publications researchers should receive credit for their production.

As with DOIs for publications before them, DataCite DOIs - established by the library community - create an open invitation for the broader community to innovate. The ability and expectation to create citable DOIs for datasets creates a global need for data repository infrastructure, and the rationale for global generalist repositories like Figshare, Zenodo, the Open Science Framework (OSF), Dryad and others.

2010: From objects to people

While the conversations to create identifiers for DOIs for publications and datasets emerged from localised homes within the research community (publishers, libraries), discussions on establishing a common persistent identifier for researchers reached out to all parts of the research community at once. In many ways ORCiD sought to establish a common research information citizenship right from the beginning, bringing together research institutions, funders, publishers, researchers(!), and service providers. ORCiDs had the potential to save researchers time and effort, but only if all parts of the research community moved together. As ORCiDs were owned by researchers the success of this initiative depended on (and continues to depend on) the constant engagement with and utility to researchers themselves.

Publishers and funders played significant roles in providing early compliance reasons for ORCiD adoption. Perhaps unsurprisingly for an identifier about people, different communities of researchers adopted ORCiDs at different rates. Adoption rates were different by different fields of research, but also by country. Regional strategies had a significant impact on the rate of ORCiD adoption, and these efforts continue today in the form of National PiD Strategies.

For services providers ORCiD provided not much as an invitation to collaborate but an imperative. Current Research Information Systems that could integrate with ORCiD could not only save researchers time by downloading relationships to publications that they had already associated with themselves elsewhere, but also help curate and add value to a researcher’s record.

The idea of an ORCiD is that it would go anywhere a researcher could authenticate. For a generalist repository like Figshare, it means that ORCiDs linked to a user’s account (along with those of their collaborators) form part of the metadata associated with the published object. The ability to associate an ORCiD with a service account provided other benefits - such as access to Overleaf accounts - as a user moved between one institution to the next.

2019: From people to institutions

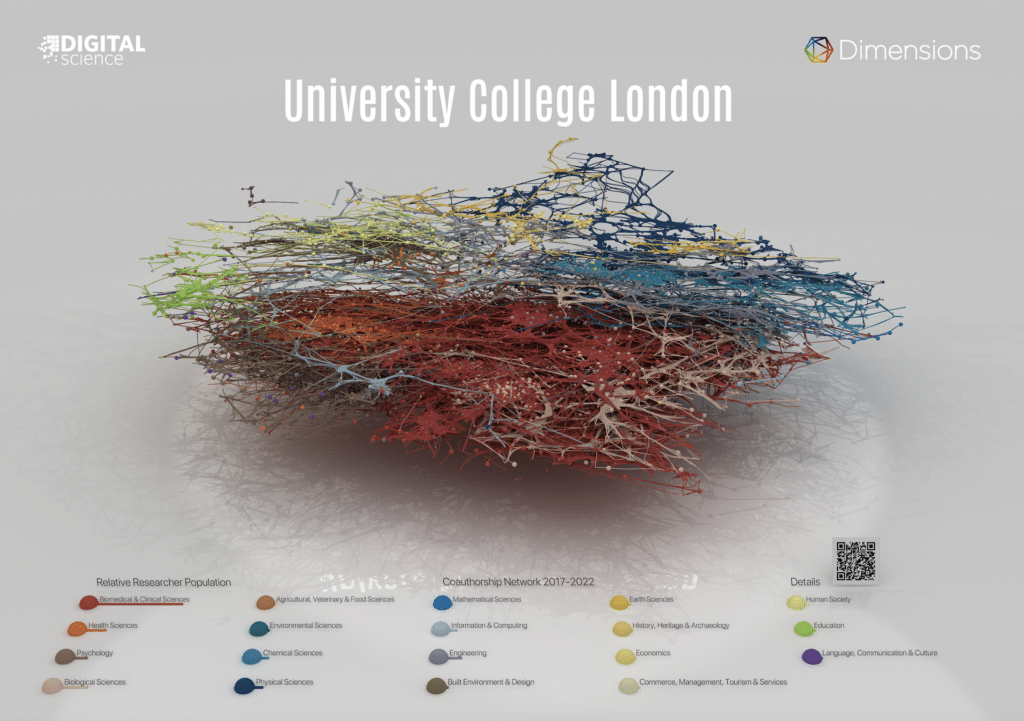

In 2019 the research organisation registry was created to provide identifiers to institutions involved in research, evolving from a well-established need to unambiguously describe and compare the research profiles of institutions. Without an open and, critically, universally adopted set of identifiers for institutions, questions of institutional assessment are limited to the boundaries of individual scientometrics data sets (such as Dimensions, Web of Science.) (For more on the creation of ROR see “Are you ready to ROR?” (Scholarly Kitchen, 2019).

Unlike other persistent identifiers mentioned so far, the relationship between a ROR and an institution is slightly more distant. The Research Organization Registry is seeded from the independently created Global Research Identifier Database created by Digital Science in order to describe all of the research institutions involved in research within the Dimensions database. A ROR is not part of an institution itself, a ROR ID is created in response to an institution participating in research.

A central use case for ROR IDs is address disambiguation. When applied retrospectively to the research corpus via algorithms they provide a common lens through which to understand institutional contributions to research. In this sense, ROR IDs share many common attributes with externally defined research classification schemes (such as SDGs or Fields of Research). The use of algorithms to connect addresses to institutions, although powerful, introduces a new discipline to persistent identifiers, namely how to deal with assertions that are likely to be true (but not always.)

Although still new, one research transformation that ROR IDs invite is the possibility of datasource independent institutional ranking systems. If we can agree on the external identifiers used to describe research, then we can swap one provider out with another and compare results.

2024: What is next? From finished objects to workflows

Finally, what research transformations await from the newest persistent identifier to reach implementation?

One of the most promising developments is the emergence of Research Activity (RAiD) identifiers and their ability to represent research activities as they evolve, recording both the participants of a project, and the outputs that they are associated with. RAiDs offer the promise of providing structure for new research outputs that an activity creates, and then finally to contributing to the discovery and provenance infrastructure necessary to build trust in research.

Reaching deep into the workflows of research, RAiDs provide a forward connection between research infrastructure of research right through to publication, as well as the promise of a backward connection back to CRIS systems and funders. Continuing a change in perspective that began with ORCiD, RAiDs challenge the entire research sector to view research metadata as an active system rather than a series of static representations.

The success of RAiDs, more than the identifiers that have come before them, will rely on the imaginations of service providers to incorporate them into their workflows, and connect through to other services. The relationship between service providers and persistent identifiers has moved from invitation, to imperative, to potential catalyst.

To demonstrate the potential of RAiDs I gave a PIDFest lightning talk/demonstration that showed the promise of RAiD workflows by using the Figshare project as a proxy for a RAiD activity definition. It demonstrated how RAiD can facilitate the flow of metadata from creation through to publication - automatically creating publication authorship details from associated ORCiDs, and providing incentives for researchers to improve their ORCiD records in the process. You can see the demonstration here.

By the end of the first day of the conference, I was delighted to be given access to the actual sandbox RAiD service. I then spent the rest of the conference in a personal hackathon of one to create an actual RAiD workflow demonstration - using a RAiD to control the users on a figshare project, and pushing author, and author contribution statements (based on project roles) into an overleaf document. You can see the resulting overleaf project here.

Of course, this is only part of the story. The agenda for PIDFest was packed with discussions on the need for persistent identifiers for instruments, samples, prizes and awards, organisms, cultural heritage objects, and more. Encouragingly, for a community that has always been about expanding the boundaries of collaboration, discussions about equity and access to persistent identifier infrastructure, and who was in the room (or online) for discussion also played a prominent role in the conference.

May the transformation continue. I am excited to see what new opportunities arise.