Subscribe to our newsletter

Open Access Books: Do we need a Plan S moment?

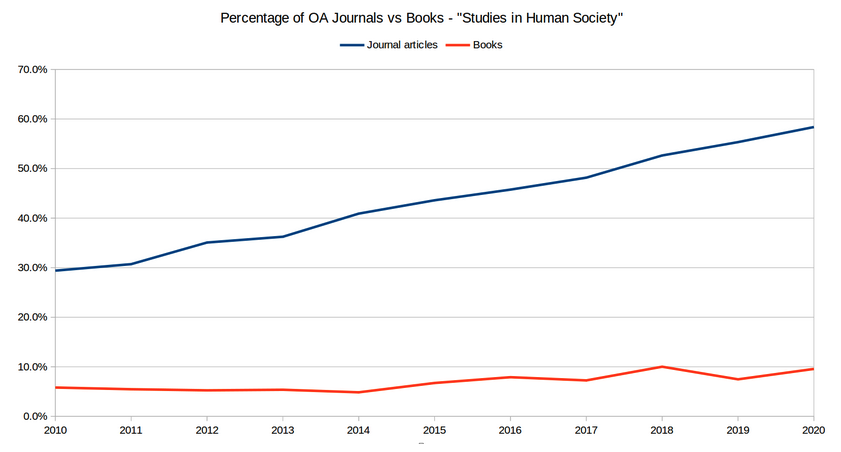

To judge from the progress of Open Access (OA) journal articles, you could be mistaken for thinking OA was the new paradigm for all research: a swift look at the charts below tells you everything you need to know.

According to Unpaywall and Dimensions, one by one the disciplines have tipped from majority-closed to majority-open. Life Sciences was the first to tip in 2013; Medical and Health Sciences followed in 2016; then the Social Sciences and Physical and Mathematical Sciences in 2017. The Humanities joined the majority open in 2020; and Engineering and Technology were at parity in 2021.

So what of books? While we can say with confidence that rates of OA publishing for both monographs and collected works have doubled over the last 10 years, the proportion of OA books remains very low, barely troubling the dominance of the traditional pay model. It’s possible to see a small increase in the last two years – which could be a consequence of more publishers making books ‘freely available’ during COVID (but, lacking a CC- licence not matching the formal status of being ‘Open Access’). Whether or not this trend continues, in a post-pandemic world, is a question that we’ll need to return to in 2024…

Books are more complex, of course. The business models are more challenging, they’re slower to write, slower to gain impact – and are considerably more diverse than journals – in language, discipline, country and publisher. Some contributors might be in receipt of mandatory OA publishing, others may be unfunded. As long as paper book sales remain strong, ‘hybridity’ will need to be baked into the model.

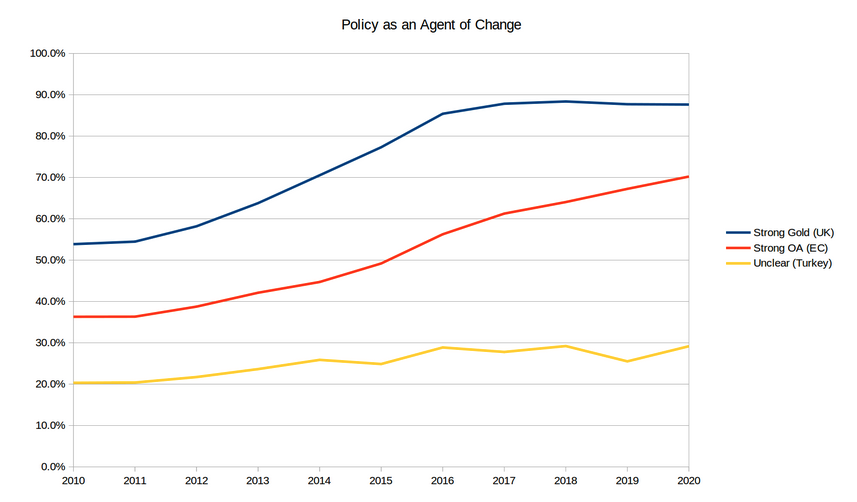

The success of OA journal articles isn’t accidental. Rather it’s the consequence of policy: the graphs below make this clear. In the UK and the Netherlands, for example, several funders have taken dramatic steps to implement Gold OA – and this can be seen in the graphs below. The European Commission, in contrast, favours universal OA, without mandating any particular model, and tends to have strong Green / self-archiving policy. The consequences of funding policy are self-evident. Other funders have softer policies, and their data has followed suit.

To understand how funders are addressing this, we spoke to three funders who are shaping the way we think about OA books, about their experiences and of their hopes for the future.

For Victoria Tsoukala at the European Commission, the reasons for books’ slow adoption of Open Access is clear: books are considerably more complex than journals, and fulfil a different role in the minds (and hearts) of scholars. The EC’s policy is clear: OA is mandatory, of whatever type works. Practically speaking, this is more challenging for books than journals. As Tsoukala says, the paper product isn’t going away, “not for us, not for our children, perhaps for our grandchildren?”, and as a consequence, she doesn’t think we’re likely to see much more progress than organic growth – hopefully reaching 50% in the next few years. ”‘But while there’s paper, there will always be hybrid,” she adds, noting that scholars will always want to keep books, read them, refer to them, be inspired by them, note them, and treasure them on their shelves. Books clearly have an emotional value that goes beyond that of the journal article.

“…while there’s paper, there will always be hybrid.”

Victoria Tsoukala, European Commission

The Wellcome Trust – long recognized as Open Access leaders – have taken a different view of OA book publishing, with OA policies evolving since 2003. According to Aki MacFarlane and Hannah Hope of the Wellcome Trust, their mission is to reduce the friction for OA book publishing to the lowest possible level. Their policy is a masterpiece of clarity, and as well as clear instructions, they’ve implemented a tool to support book publishers to make their content available and compliant.

Neither the EC or Wellcome Trust publish a fixed Book Processing Charge for OA books. In contrast, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) does: $5500, to be paid directly to the publisher, with $500 of that to go to the author. Brett Bobley of the NEH shared more details of their “Fellowships Open Book Program”, a project referred to as their ‘flagship program’. Curiously, their policy takes a different view of the payoff between sales and access: US-based publishers are welcome to ‘OA’ their books, and apply for the money, at any stage. The implication is that publishers are able to sell their books, and when they’re ready, make them available OA – as long as it’s through a recognised platform. The NEH has a good track record of working with publishers and scholars to develop policies, with several university presses being consulted with.

All three of the funders acknowledge a number of core issues: the complexity (and consequent friction) of the socio-economic role that books play, and the issue of discoverability.

This blog has previously reported the challenges of visibility and discoverability experienced by the scholarly monograph, estimating that approximately half of published output takes advantage of the open scholarly infrastructure systems, such as DOIs and ORCIDs.

Even organisations that mandate OA – and report strong compliance – have been known to struggle with discoverability. The EC’s metadata policy mandates use of DOIs and ORCIDs; the NEP mandates publishers to make their books available on at least two major digital distribution services; Wellcome mandates the use of NCBI Bookshelf and Europe PMC. Nevertheless, their aggregated percent of OA books from the last five years has not yet reached 2/3rds of funded books, these numbers falling short of what we estimate as being eligible.

The world of scholarly publishers is considerably more diverse than that of the journals world, with many hundred small and university presses producing a considerable percentage of the world’s academic book output. And this area is getting more complex, with many new business models being developed.

“We hope that the next 10 years sees a similar change for books, as the last decade has seen for journals, while preserving the cultural and social role of the scholarly book.”

Mike Taylor, Digital Science

All three of the funders interviewed emphasised their support for publishers, and the development of new business models: a point that came up in all three was the need to ‘assuage their fears’, ‘to reassure them…’, ‘to lower the bar…’ Publishers play an essential role in the development and distribution of the scholarly book, and OA or not, no-one sees them going away.

For me, it’s gratifying that three such important funders take the book seriously, and acknowledge this final fact. Much work still needs to be done to encourage the growth in OA publishing for books – as we’ve previously covered, OA books get far higher uses and achieve much higher rates of sharing and readership than non-OA books, while not noticeably having reduced sales – and these three funders are certainly playing a strong role in changing the environment.

As we have seen: policy drives change. In Figure 2, we can compare the change in OA for three countries with (respectively) strong, moderate and weak OA policies for journals – without similar clarity of purpose and policy, OA book growth is likely to continue in its current state. We hope that the next 10 years sees a similar change for books, as the last decade has seen for journals, while preserving the cultural and social role of the scholarly book.

This will not happen without clear policies.

About the Author

Mike Taylor, Head of Data Insights & Customer Analytics | Digital Science

Mike is an innovator in scholarly metrics and social impact. Prior to the development of altmetrics, he was working to understand how researchers were using emerging social media networks and other platforms to exchange information. He has been involved in many open initiatives during his career, most notably contributing to the architecture of the ORCID repository and API prior to its launch.