At the start of my PhD in Stem Cell Biology, I was not aware of Open Access despite Open Access journals being a thing since the late 1980s. arXiv came along in the early ‘90s, followed by PubMed Central and the first commercial OA journal, Biomed Central in the late ‘90s. PLOS launched in 2001, but it wasn’t until PLOS ONE the conversation sparked in my lab.I was introduced to Open Access publishing not because of the ideals of access for all, but the fact that PLOS ONE does not value the perceived importance of a paper as a criterion for acceptance or rejection and therefore our lab could publish lots of our research there. Perfect in the publish or perish world of academia.

So, it is truly remarkable that just a decade later, the majority of publications were Open Access publications. This idea that research can be akin to a large ship that is slow to change course appears to be outdated.

Number of Open Access Publications per year

More recently eLife has taken a huge leap in reviewing its model of publication and becoming a hybrid pre- and post- peer review publishing house.

“We will publish every paper we send out for review as a Reviewed Preprint, a journal-style paper containing the authors’ manuscript, the eLife assessment, and the individual public peer reviews.”

This is pretty much a professionalised version of Stevan Harnard’s Subversive Proposal, which is now nearly 30 years old and called for preprints on FTP servers as a way to create global Open Access. The difference is that the time is right. eLife has the advantage of online only infrastructure and consumers. The tools that allow eLife to thrive were not available 30 years ago. So 30 years on, was Harnad’s proposal right and does eLife finally have the answer?

Trust comes first

Recently, I have experimented with visualising optimal academic dissemination. I soon realised my scoring system below was flawed – as trust in research trumps the content being open, quickly disseminated or cost effective. What it did highlight is that newer types of content, such as data or code publishing, benefit from not having legacy workflows, sustainability models or the concept of prestige. The cost and complexity to make data publishing ‘trusted’ is orders of magnitude less than to make traditional paper publication fast, open or cost effective.

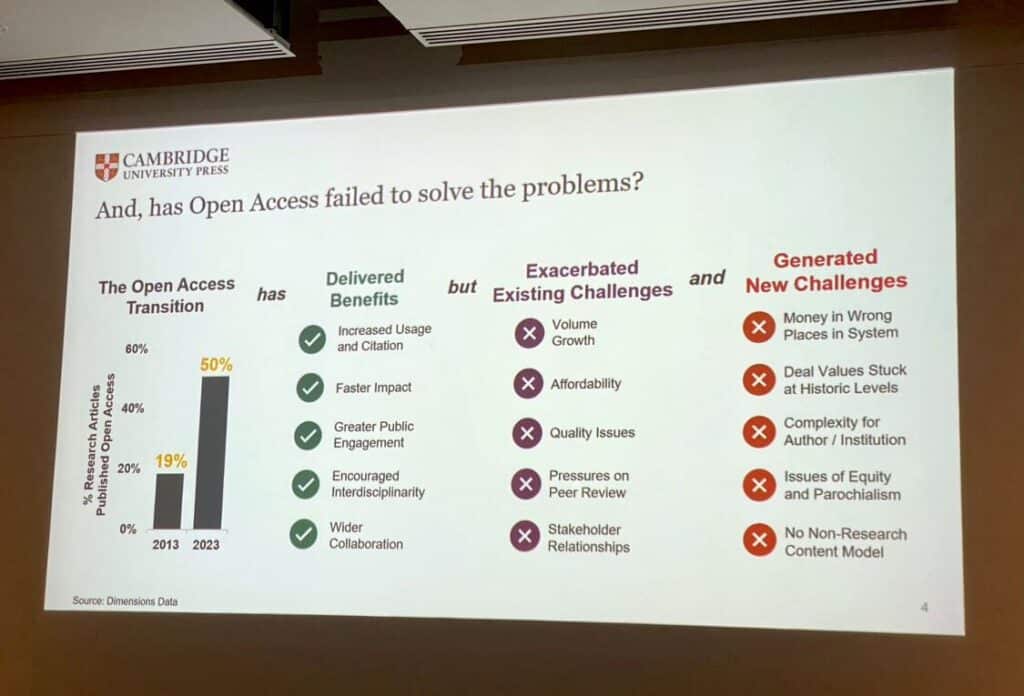

Herein lies the problem, though. Treating each of these issues as equal can lead to propagation of non-trustworthy and even false research (sometimes with an agenda). Trust needs to come first. At UKSG this month, Chris Bennett of Cambridge University Press & Assessment highlights what has happened in attempting to fix scholarly publishing by ‘solving for x’, where x is ‘open’.

Open Access publishing is complex, partly because that is what it has become, a business model. If we solve for x, where ‘x’ is maximising article processing charges (APCs), we see an explosion of content, a lot in the form of special issues (invited papers). I would make the case that we are currently publishing too many papers.

Gates-keepers?

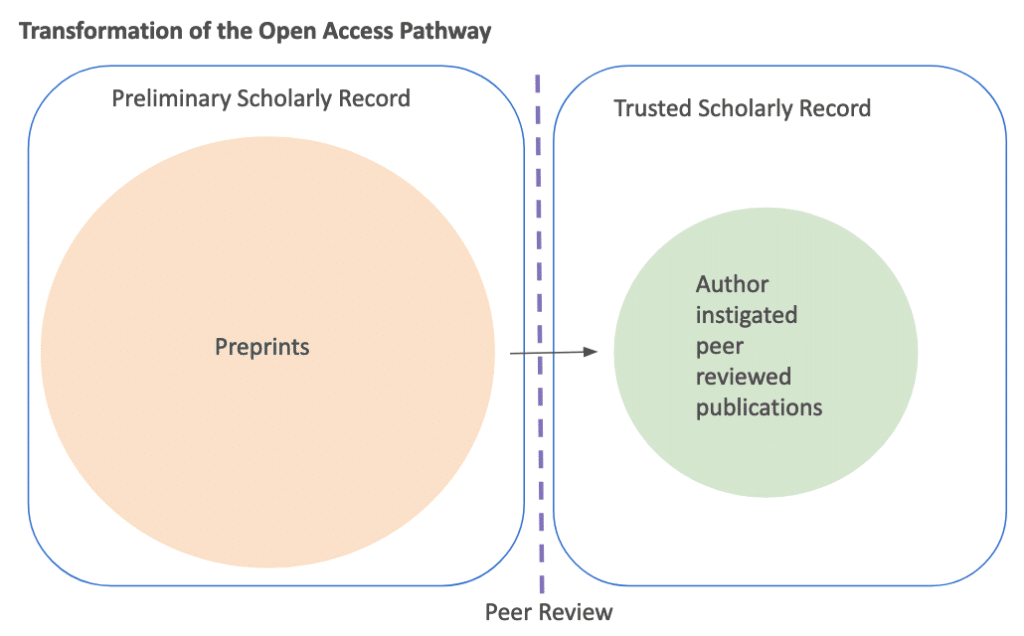

So perhaps the answer is to move all of the publishing to the other side of peer review and transform the way we talk about the Preliminary Scholarly Record and the Trusted Scholarly Record. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has updated its Open Access policy from January 2025 in a way that lends itself to this transformation:

- “Requiring preprints and encouraging preprint review to make research publicly available when it’s ready. While researchers and authors can continue to publish in their journal of choice, preprints will help prioritize access to the research itself as opposed to access to a particular journal.

- Discontinuing publishing fees, such as APCs. By discontinuing to support these fees, we can work to address inequities in current publishing models and reinvest the funds elsewhere.

- We will work to support an Open Access system and infrastructure that ensures articles and data are readily available to a wider range of audiences.”

In my opinion, the Gates Foundation is taking us in the right direction. eLife is already there. The problem lies in the murky middle. Preprints shouldn’t be treated as academic facts by the general public and news media. Researchers in the field can make their own decisions on whose research they trust in their field and why, as has been the case in arXiv for years.

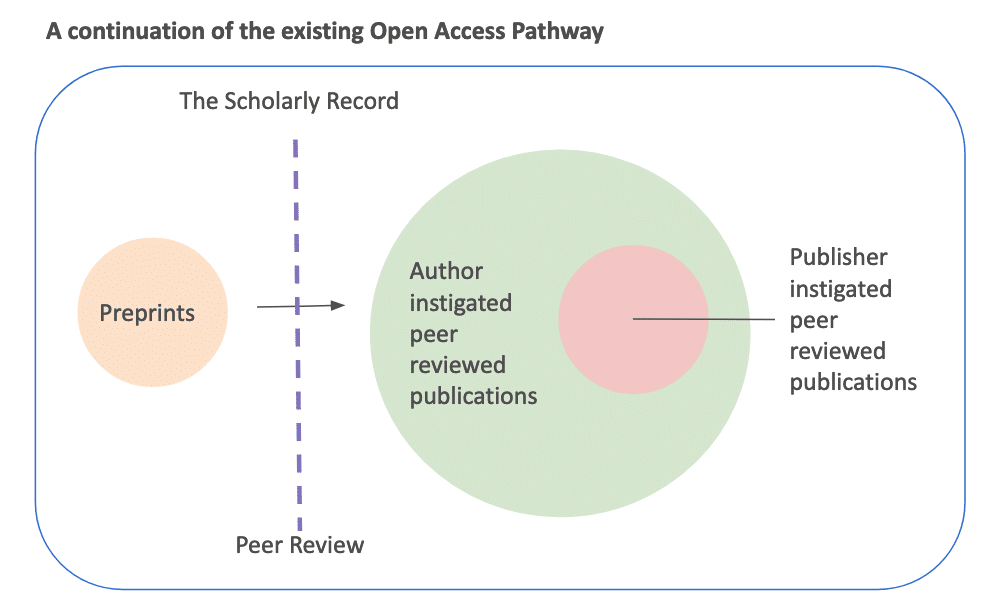

If we compare the path we have been on with regards to Open Access with some of the newer experimentation, a proposed transformative pathway emerges. Currently, we do not have a preprint for every paper. The Scholarly Record is made up of preprints, author instigated and publisher instigated peer reviewed publications. Not all peer-reviewed publications are Open Access.

If all papers were published as preprints before being submitted for peer review, the problem of un-checked research being picked up by news media or conspiracy theorists could cause a problem. Therefore, having community wide standards around presentation of and language describing the papers pre- and post- peer review should be established. We should have a ‘Preliminary Scholarly Record’ and a ‘Trusted Scholarly Record’. This author argues that a transformation of the Open Access pathway would lead to many benefits compared to the existing model. This is very inline with a proposed “Plan U” – “If all funding agencies were to mandate posting of preprints by grantees—an approach we term Plan U (for “universal”)—free access to the world’s scientific output for everyone would be achieved with minimal effort” (Server et al.)

| A continuation of the existing Open Access Pathway | Transformation of the Open Access Pathway |

| Pay to open | Open in the preprint/green form by default |

| Major cost is at the publication level | Major cost is at the peer review level |

| Indeterminate innovation in the speed of research dissemination | Research disseminated by default, but with the caveat that misleading, opinionated and unfactual research is published fast |

| Large corpus of trustworthy research | Large corpus of trustworthy research |

| Ambiguity for the general public as to what is rigorous, peer reviewed research | Clear delineation between preliminary, unchecked research and what is rigorous, peer reviewed research |

Automatic for the people

The transformative approach also opens other areas to focus innovation on. I want to fix peer review. This is the area that I think can have the most impact in academic publishing in the next 20 years – that is not already being aggressively pursued (eg. data publishing). By establishing transparent and open quality checking of academic content, both humans and machines will be able to distinguish genuine research from fake, embellished or exaggerated findings. Automating trust markers can contribute to the bigger picture of framing.

Society will advance at a greater rate if academic research is published faster (maybe even if fewer papers were published faster). Every current model falls down at the point of peer review. Peer review is largely unpaid, and the incentive structures for doing it mean that senior researchers often pass on the work to those less experienced and the benefits to the researcher themselves are a grey area, if they exist at all. As such peer review is slow, a burden. This means that we cannot achieve the Shangri-La of “trusted, fast academic publishing”, without overhauling peer review. My desire for the next transformation in Open Access is to solve for “peer review”. You could argue we will just make things even more complex. However, going back to my Optimal Academic Publishing Model, I argue that it is much more cost effective and less complex to add trust to the existing open and quickly disseminated preprints than the alternative. That is, to reverse engineer openness and fast dissemination to the closed access publishing model.

Open Access has been transformative. That transformation cannot stop here. The job is half done.

References

Hanson MA, Barreiro PG, Crosetto P, Brockington D (2023) The strain on scientific publishing. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.15884

Sever R, Eisen M, Inglis J (2019) Plan U: Universal access to scientific and medical research via funder preprint mandates. PLoS Biol 17(6): e3000273. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000273