TL;DR Summary

Despite recent disruption, social media platforms and Twitter in particular remain a valuable space to build research communities and break down barriers to inclusion and cross-disciplinary research. Data from Altmetric shows us that, despite some high-profile defectors, the volume of research being shared on Twitter has not been impacted by recent events. If we are to find a new space for research engagement, what would we like to keep and what would we like to see more of?

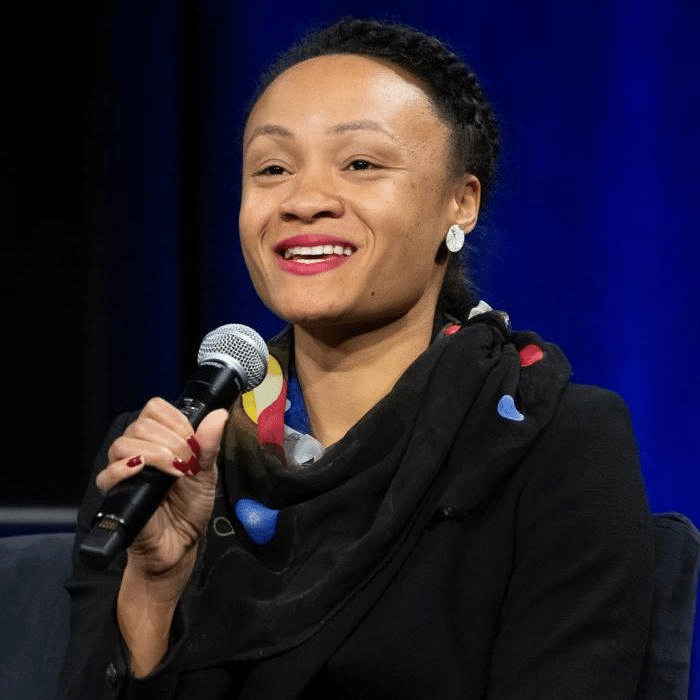

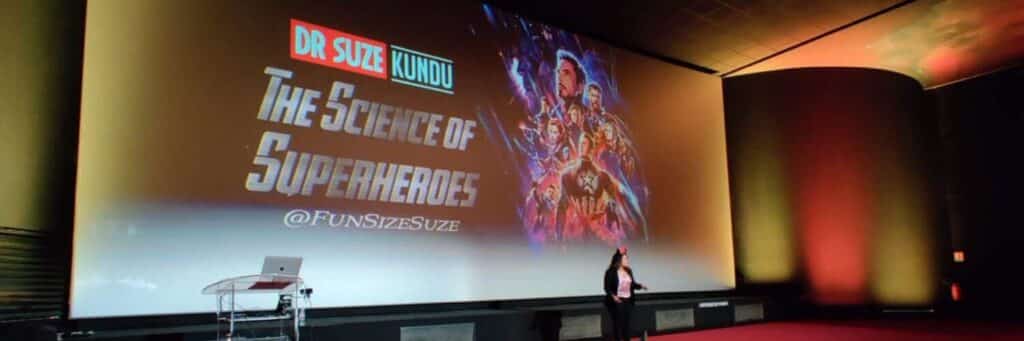

The “FunSizeSuze” Origin Story

Back when I was an undergraduate chemist at UCL I quickly picked up the nickname “Fun Size Suze”. This was in large (or small?) part due to the fact that my 7-foot-tall Swedish lab partner and I could successfully navigate the trials and tribulations of column chromatography without the trauma experienced by those closer to the middle of the height bell curve. Back then, as a lowly undergraduate, I had little online social media presence beyond a MySpace account to carefully curate my social circle and rank my favourite bands, and a Bebo account to excitedly share digital photos of nights out.

Around the time I started my PhD Facebook had risen in popularity and quickly became THE social network everyone was on. I eventually, and rather reluctantly, joined for a while and though I remember some friends sharing their research conference adventures, privacy settings meant that most people chose only to share things with their pre-vetted closed circle of friends, many of whom may not necessarily be the intended target audience for such content.

Hot on Facebook’s heels came Twitter and with it, a public profile from which to share likes, dislikes, work achievements, and cat pictures – this is still The Internet after all. Curiosity finally got the better of me and in May 2011, as my final PhD experiments were wrapping up, I gave in and created an account. When faced with the prospect of having to choose a user name, and given the fact that my heritage comes from one of the most populous countries in the world with only so many names to go around, I was far from original enough to use my first name, last name, or a combination of the two without having to add a bunch of numbers after my name – something which is best avoided in today’s social media climate.

In a panic, I chose my nickname as my username, and @FunSizeSuze was born. Of course, it was never supposed to stick, but almost twelve years, 12 thousand followers (why?!), and one now-revoked freebie Blue Tick later, it has rather stuck. I recall meeting the now-former Director of the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology for the first time “IRL” and being greeted with that very nickname, as he yelled it across the wood-panelled reception room. My Twitter handle had become shorthand for me, my personality, and my reputation.

Finding Your Tribe

For me, and anecdotally for many others too, social media and Twitter, in particular, has become a place to “find your tribe” – overcoming geographic barriers to find people whose experiences and values align most closely with your own; safety in numbers; a place where you can feel you belong; your team, your allies, your friends. Research can be quite isolating, especially when you’re stuck in the lab or at your computer, working on something quite different to those around you. Twitter has been a perfect platform through which researchers can create those connections and forge communities of practice.

Those communities of practice are not just limited to research topics. Many groups of people that find themselves underrepresented in research have found a voice by finding each other, sharing their challenges and successes, and raising the collective volume of their voices so that they can be heard, and so that the unique challenges they experience within an inflexible research landscape can be appreciated and understood. One simply needs to look out for hashtags like #WomenInSTEM or #BlackInNeuro to read about people’s lived experiences and also to learn about leading researchers that you would not necessarily have heard of within the confines and constraints of academia.

Twitter is also a place where everyone has a voice. That same research culture tends to celebrate the big-name researchers winning huge grants. Success snowballs and, as these researchers gain more exposure, they are afforded more opportunities to showcase their work, which often leads to more research funding. Given how much academia ties research success to such things, it makes sense to establish a researcher profile of your own. By sharing research on Twitter, a researcher can not only reach people they could not otherwise reach but also expose people to their work in complementary disciplines, thus building their profile as a key opinion leader in their field. Engagement with research shared on social media can be measured using alternative metrics, or altmetrics. The democratisation of profile building on social media may have resulted in related research success for more Early Career Researchers and for researchers engaging the public and policymakers with their research. The addition of a quantifiable indicator of engagement goes some way to proving the value of such dissemination of research, raising the profiles of many more researchers and widening the playing field of potential success.

Social Media to Challenge the Status Quo

Twitter has also been adopted as a public platform to announce novel developments, celebrate successes, share advice, and make noise where positive disruption is required to challenge the status quo and move things forward. One example of such anarchy springs to mind immediately. Back in 2012 the European Commission, in their unchecked wisdom, chose to produce the now infamous video, “Science – It’s A Girl Thing”. It was everything you would hope a video encouraging half the population to consider science, technology, engineering and maths could NOT be, from the video’s title written in pink lipstick to the strange notion that to be a woman in scientific research required you to also be a part-time model.

Of course, many of us objected to this, and some with the means to counter it through action. Thus the 2013 Science Grrl calendar was born, showcasing actual women in science, technology, engineering and maths, and some men as allies too. The calendar was sold to raise money and awareness for the issue of women being put off studying STEM subjects at university and beyond – and with a video like that, was it any wonder?

Social Media for Breaking Down Barriers

Twitter is where communities are built and where conversations happen. You would be hard-pressed to think of a conference that has taken place in the last few years that hasn’t had a hashtag that can be followed. These allow you to not only document and share your own thoughts and opinions of proceedings, but also catch up on parallel sessions you may be missing. I have been known to read up on the hashtag of conferences I have been unable to attend and, though the coverage is biased toward the opinions of those more prone to sharing their commentary, it is a great way of opening up discussions to the broader community, some of who may wish to be in attendance but cannot for financial or bureaucratic reasons, or due to caring responsibilities. In this way, Twitter has supported access to conferences – to paraphrase Hamilton, everyone can be in the room where it happens.

When the COVID-19 pandemic first took hold in 2020, many conferences successfully pivoted to an online-only format. Though some conferences opted to create their own attendee-only platforms for discussion (and the many semi-virtual reality platforms that popped up to help us socialise in ways that would simulate conference mingling – looking at you, GatherTown), Twitter was buzzing with conference activity, and allowing many more people to take part in the conversation.

The Future of Social Media for Research

With so many positive ways in which Twitter can impact research, it is somewhat unnerving to see so much disruption in recent weeks and months. While Twitter is a force for inclusion, it is also increasingly a platform for abuse. Communities of practice have also formed around the debunking of science, and to breed deliberate misinformation and unintentional disinformation. Twitter pile-ons are an all too frequent occurrence. And, of course, the self-curation of information we all choose to consume through the people we find affinity with and follow can often lead to an aspect of echo chamber formation. This confirmation bias leads us to falsely believe that people generally agree with what we are thinking when it can breed disengagement with society as a whole. Those of us that were floored by the Brexit referendum result know this only too well.

Given that Twitter has been on a precarious footing in recent months, should we assess the role that Twitter plays in research? Can other platforms provide the same levels of engagement and support for career development, exposure, networking, profile-raising and community-building?

There was what could be perceived as a large movement away from Twitter and over to Mastodon towards the end of 2022. However, the two platforms are not the same. You cannot reach the same people unless everyone is following you and, while the independent servers are much like communities of practice, there is the risk of developing an echo chamber and never reaching those from outside your own discipline, which is where so many of the best and most innovative research is coming from.

So how else can we keep using social media as a force for good in research? Facebook demographics are useless and people rarely post publicly, if they are even on the platform at all. Instagram is still mostly food photos, BeReal seems to be the place where folks take photos at the gym, usually sweaty from having raced there and not because they were working out already! TikTok has been used successfully to share some research ideas with groups of people that are traditionally much harder to engage with, but if we’re going to all get on board with that, we’re going to need more step-by-step dance tutorials…

Twitter is important. It’s a community that you have built, and no other community is like it. What do we do when a key community platform is at risk? Should we leave in our droves to protest against the current ownership and the influx of formerly blocked bad actors, or should we remain and fight from within? How many have left Twitter already and how has it impacted research engagement? Data from Altmetric shows us that, despite some high-profile defectors, the volume of research being shared on Twitter has not been impacted by this. If we leave, what do we need in a new social media platform? And what happens to all the valuable content held on such platforms, such as conference discourse? Whose responsibility is it to preserve this knowledge for future generations?

Share your thoughts with us, whichever platform you’re on. We’d love to hear from you.

If you’ve enjoyed reading this article and would like to chat with us about featuring your research, founder story, or other interesting topic, please let us know — we’re always happy to hear your ideas and suggestions!