Subscribe to our newsletter

A Conflict of Interests – Manipulating Peer Review or Research as Usual?

In seeking to define morality and moral actions, the Catechism of the Catholic Church states in paragraph 1753 that, “A good intention (for example, that of helping one’s neighbor) does not make behaviour that is intrinsically disordered, such as lying and calumny, good or just. The end does not justify the means.”

Stephen Sammut, PhD

Science, Scientific Method, and Politics

It is tempting to think of science in the abstract as objective and pure based on rigorous analysis of empirical evidence. Conversely, politics might often appear less structured and more chaotic, based on subjective values and driven by interest groups and compromises. However, both are human endeavours – neither science nor politics functions solely in the abstract. Both are influenced by biases that are often not evident or transparent to the external observer. The scientific method is one mechanism of checks and balances used to curtail undue, inappropriate, or political influence on science.

The scientific method teaches researchers to be sceptical and revolves around the performance of rigorous experiments, the collection of data, and the unbiased presentation of results in a format with sufficient explanation and transparency that peers may review, question and reproduce the results. In contrast to the platonic ideal of the scientific method, scientific enterprise in practice is more complex and nuanced. It involves many scientists with complex relationships and drivers, research institutions with needs, funding agencies with stakeholders, and publishers with shareholders. All operate according to their incentives and values. And they compete for support and funding within a society shaped by a complex, dynamic, and multi-stakeholder landscape.

Politics also operates in what often seems like a detached or parallel universe in which decisions are reached via a mix of scientific and economic evidence, the needs of the general population, and sometimes by influential interested individuals, groups, and companies.

In reality, science and politics have always been intimately connected, and neither works in practice as they do in theory. Science is political, and although politicians and lobbyists may not use the scientific method, they use science. Science may be used politically but what is crucial is to ensure that politics and subjectivity do not interfere with the scientific method.

Peer review is a check within the framework of scientific communication, but it is not the check. It is, however, the one salient to this story.

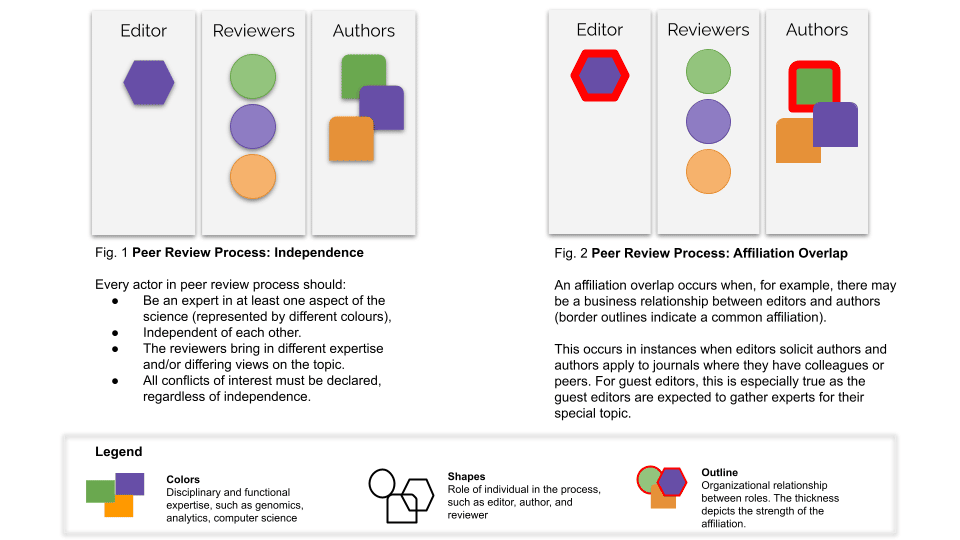

Existing since the 1700s, peer review provides an opportunity to validate scientific research. Growing to an accepted norm about 50 years ago, peer review ideally operates by having knowledgeable, independent experts review scientific research. Most people reading this article understand the broad workings of peer review. The peer reviewers should be independent of each other and experts in a topic covered in the paper (Fig. 1). The reviewers offer insight into the quality of the subject and the strength of the methods. In theory, all actors should be independent of one another, but in practice, this is rarely the case. ‘Peers’ means there should be some overlap among people and their knowledge – the people taking on the review must have the capacity and capability to form a thoughtful critique of a given piece of work. To that end, the editors, peer reviewers, and authors are often part of the same scientific society or even organisation (Fig. 2).

Because the peer review process can vary and has not been standardised, the difference between optimising and manipulating the process may not be clear. The first is a grey area of knowing how the system works and fine-tuning the approach for professional gains. The latter refers to understanding how the system works and stepping over community boundaries of acceptable practices. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) offers guidance on peer review. In contrast, the International Committee on Medical Journals Ethics (ICMJE) clearly states: “Reviewers should declare their relationships and activities that might bias their evaluation of a manuscript and recuse themselves from the peer-review process if a conflict exists.”

See what you think in the following actual case.

Manipulation of Peer Review or Research as Usual?

We take a controversial 2022 research publication as our subject in this case study. However, the nature of the research is not critical to our discussion but rather the scholarly communications process and its integrity – specifically the character of the peer review process. We abstract crucial elements of this case and highlight the most salient and relevant issues. We look at this case without revealing the topic area, as this can be a distraction to the point at hand.

We identified the current case not via a specific literature search (i.e., a topic-based approach) but rather by studying variances in trust marker signatures (e.g., hypothesis, conflict of interest, funding statements) across a range of literature, being blind to the subject area. This paper fell outside a specified range of norms for several trust markers. For example, the study purpose did not use the drier language typical for research in this area which, combined with the lack of a funding statement, raised an initial suspicion.

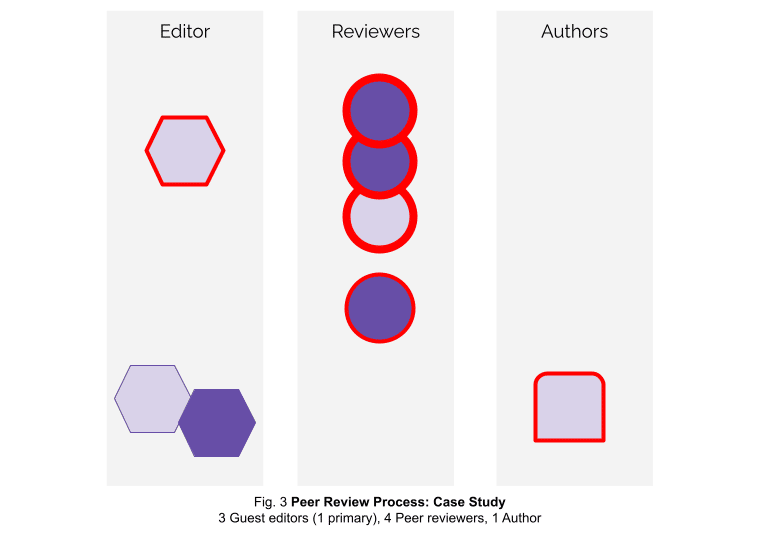

Our chosen case involves three guest editors, four peer reviewers, and a single author, all of whom appear to be closely affiliated either in the community or through their professional affiliations. Three peer reviewers work directly for a single private organisation (“Organisation X”). One of the guest editors, the fourth peer reviewer, and the author are all affiliated with Organisation X. However, only one of the peer reviewers listed an affiliation with Organisation X. The other two guest editors are closely aligned with the principles of organisation X but are leaders in similar organisations. Only one of the peer reviewers originated from a traditional academic research institution. The other peer reviewers did not have affiliations with traditional research institutions. Nuances of peer review are described elsewhere.

Generally, we expect reviewers to have varying and overlapping knowledge and training in related fields for proper peer review. For example, having a topic expert and a statistician in economics would overlap fields with different areas of expertise. Additionally, we expect to see a balance of knowledge and affiliations across editors, peer reviewers, and the author. Affiliations may overlap in narrow fields with small or cutting-edge communities, but the case in question is not a narrow field. Aligned interests raised a flag, though.

In summary, the expertise of guest editors, peer reviewers and the author appears to overlap, as do their perspectives, affiliations, and alignment of interests. (Fig. 3).

Objectively and without specific context, many questions come to mind: When would these overlaps be acceptable while maintaining a robust commitment to research integrity? What other information do you need to know to make that decision? Will the peer reviewers be able to critically and independently evaluate the science within the paper?

The Case: When are commonly held interests too overlapping for peer reviewers?

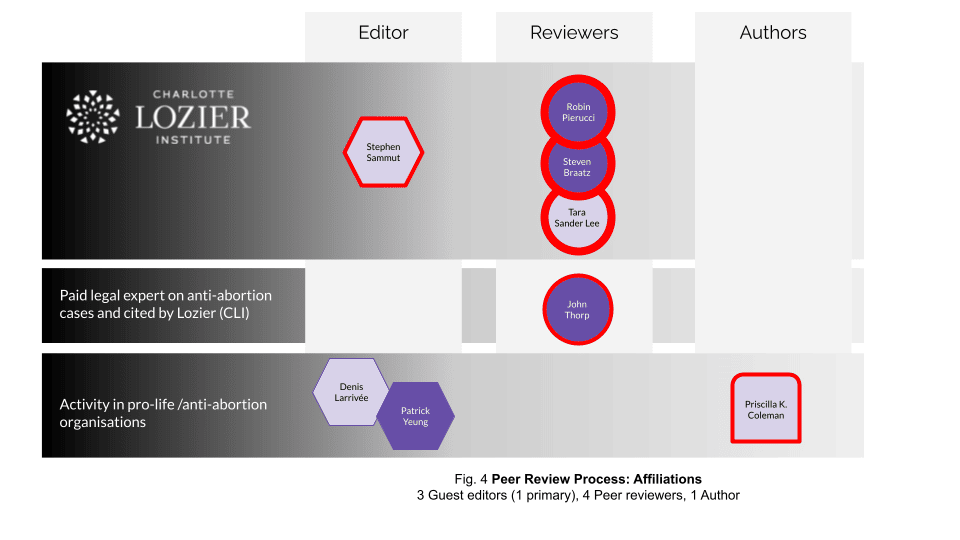

The case mentioned above is the recently published (and now retracted) paper in Frontiers in Psychology, “The Turnaway Study: A Case of Self-Correction in Science Upended by Political Motivation and Unvetted Findings” (Coleman, 2022). This paper sought to criticise The Turnaway Study, a landmark study describing “the mental health, physical health, and socioeconomic consequences of receiving an abortion compared to carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term”. The article came to our attention through algorithms where trust markers appear irregular. This alert suggested we search social media and PubPeer, where a corroborating signal was found. In addition, the signal indicated we should look closer at the trust markers within the article to ensure due diligence of scientific processes was followed. Because Frontiers published the names of reviewers and their declared affiliations, this transparency allows researchers to review their associations in the context of the peer review process and assess the potential for insularity.

Coleman’s article, retracted on 26th December 2022, and described in Retraction Watch, appeared in the journal as part of a research topic (a curated article collection, somewhat like a special issue), Fertility, Pregnancy and Mental Health – a Behavioral and Biomedical Perspective. This research topic was led by three guest editors at Frontiers, while the specific Coleman article had four peer reviewers. All peer reviewers state different affiliations, but three are with the same anti-abortion Charlotte Lozier Institute (CLI), which states on its website that it is: “the preeminent organisation for science-based pro-life information and research.” Moreover, the editor charged with reviewing this article is affiliated with CLI. However, most associations were not disclosed (see table and Fig. 4).

| Name | Role | Stated Affiliation | Affiliation with Potential for Conflict of Interest | Cited by CLI* |

| Stephen Sammut | Guest Editor | Franciscan University of Steubenville | Charlotte Lozier Institute, Former member WECARE** | 1 |

| Patrick P Yeung | Guest Editor | Saint Louis University | St Louis Guild of the Catholic Medical Association | – |

| Denis Larrivee | Guest Editor | Loyola University Chicago | International Association of Catholic Bioethics | – |

| Robin Pierucci | Reviewer | Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Western Michigan University | Charlotte Lozier Institute | 7 |

| Steven Braatz | Reviewer | American Association of ProLife ObGyns | Charlotte Lozier Institute | 4 |

| Tara Sander Lee | Reviewer | Charlotte Lozier Institute | Charlotte Lozier Institute | 8 |

| John Thorp | Reviewer | Carolina Asia Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | Crisis Pregnancy Center Director | 7 |

| Priscilla K. Coleman | Author | Human Development and Family Studies, Bowling Green State University | Former Director, WECARE** | 4 |

**World Expert Consortium for Abortion Research and Education (WECARE).

CLI presented an amicus brief (an expert opinion) to the US Supreme Court on 29th July 2021 in support of overturning the court’s earlier decision to uphold the outcome of Roe vs Wade, which had asserted for the past 50 years that women in the United States have a constitutional right to an abortion. Moreover, one of the peer reviewers for the Coleman article, Robin Perrucci, MD, an associate scholar at CLI, filed a separate amicus brief on 20th July 2020 with the Life Legal Defense Foundation in the Dobbs v. Jackson Health US Supreme Court case. Priscilla K. Coleman directed the World Expert Consortium for Abortion Research and Education (WECARE), where Stephen Sammut was among ten other members. John Thorp’s legal testimonies on abortion have previously come into question, and he has been the medical director of an anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centre for over 40 years.

Giving Air to Unethical Practices

We are passing no comment on the area of research involved here since this is a highly emotive area for many. However, this peer review process is of clear interest in research conduct and integrity viewed independently of the underlying research. Furthermore, our simple example highlights the potential for institutes, peer reviewers, or authors to translate aligned political interests into scientific influence.

A decision-making majority of editors and peer reviewers are members or affiliates of organisations with publicly stated aligned interests; this process does not meet the standard of the independent, unbiased scientific method.

Allowing this paper to be published in the scholarly record provides a sense of unwarranted legitimacy to the arguments. We hope that publishers will learn from this experience and take action.

For those responsible for the paper, including its undeclared conflicts of interest, the end goal of having a ‘peer-reviewed’ article does not justify the means used to get there.

Note: Part of this analysis was presented at the eResearch Australasia conference in Brisbane, Australia, October 2022.

About the Author

Dr Leslie McIntosh, Vice President, Research Integrity | Digital Science

Dr Leslie McIntosh PhD, MPH is the VP of Research Integrity at Digital Science and dedicates her work to improving research and investigating and reducing mis- and disinformation in science. As an academic turned entrepreneur, she founded Ripeta in 2017 to improve research quality and integrity. Now part of Digital Science, the Ripeta algorithms lead in detecting trust markers of research manuscripts. Dr McIntosh works around the globe with governments, publishers, institutions, and companies to improve research and scientific decision-making. Dr McIntosh served as the executive director for the Research Data Alliance (RDA) – US region and as the Director of the Center for Biomedical Informatics at Washington University School in St. Louis. She has given hundreds of talks including to the US-NIH, NASA, and World Congress on Research Integrity, and consulted with the US, Canadian, and European governments.