Subscribe to our newsletter

Research in the second Elizabethan era: A platinum age for the Commonwealth and the UK

From physical empires of the past to information and virtual empires in the modern era, the last 70 years have borne witness to astonishing change in both research and science and how they are communicated. But where have these shifts occurred, and what do they tell us about the future? And what will be the legacy of Elizabeth II’s long-lasting reign for science and technology?

In the UK, Commonwealth countries, and around the world, people have mourned the passing of Queen Elizabeth II. For many, she will be remembered as a dedicated public servant who gave her support to charities and good causes, raising their profile and giving them a voice that helped them to be noticed in the world. For a good deal more than half a century, successive Prime Ministers have regarded her as a giver of context and a provider of a safe space to air concerns and discuss the challenges of the day that they could share with no one else. She has been widely recognised as a constant in our lives and, by some, as the embodiment of all things British in a changing age. An instantly recognisable figure, the Queen has played the role of an observer of that change, unable to be actively involved in politics but having privileged access to politicians, celebrities and changemakers globally during a period of great change.

Image credit: Ocean Outdoor.

In this brief commemoration in honour of Her Majesty, we wanted to reflect on the changes in research and, in particular, in scientific research that have characterised the modern Elizabethan era. The Queen was crowned in the same year that Watson and Crick (with the significant help of Franklin) published their paper on the double helix structure of DNA in 1953. Over the intervening 70 years, the UK has not only remained at the forefront of research, but has made contributions that have been key to shaping the emerging exponential industrial revolution. From Sir Tim Berner-Lee’s pioneering work around the World Wide Web in the late 1980s, to the London-based DeepMind team who solved the protein-folding problem with AlphaFold, the UK has been the home to some of the greatest scientific advances of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries.

Like her great-great-grandmother Queen Victoria, Queen Elizabeth married a man who had great interest in, and who consequently was a great supporter of, science and technology. The Victorian era is one that is remembered not only for empire but also for innovation and its technological contribution to the world, and we suggest that the second Elizabethan era will be viewed similarly in this respect. In 1952, the UK produced around 2% of the world’s research output and the broader Commonwealth of Nations, with which the Queen is so intimately related, around 3%. As of 2021, the UK produces around 4% global research and, together with other Commonwealth countries, around 14%.

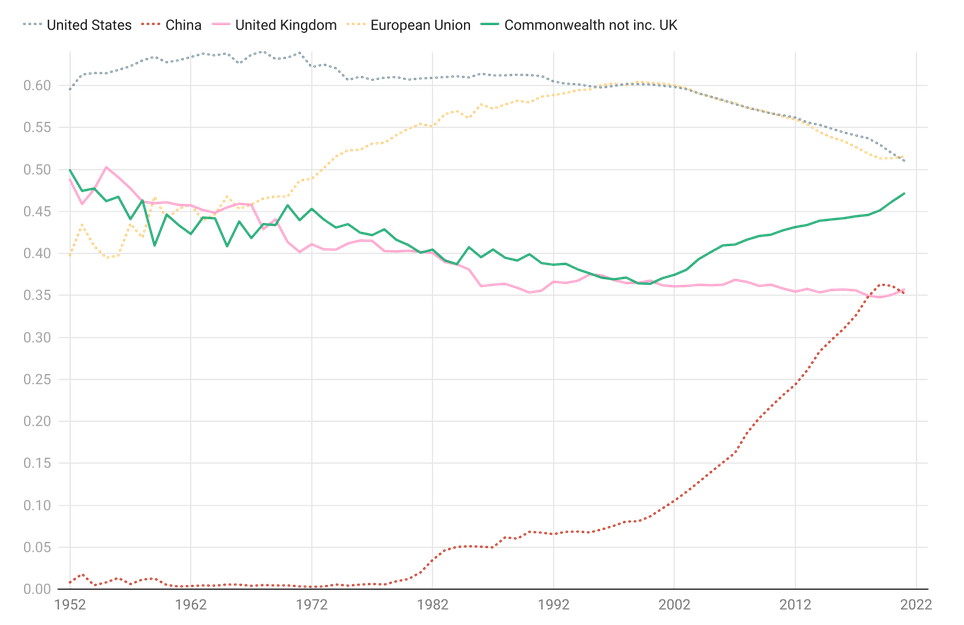

The influence of the Commonwealth on the world stage often goes unseen but network effects are powerful in today’s world. Figure 1 shows relative global influence on research of each country or set of countries using a technique that we’ve developed at Digital Science over the last few years based on the eigenvector centrality network measure. The core of the idea is that research volume and research citations only show a superficial picture of research strength. Research is becoming an increasingly collaborative pursuit and success is born of finding the right people with which to work. Eigenvector centrality calculated in the way shown here mixes volume, citation and level of collaboration into one metric that, we argue, is an interesting proxy for influence. In the figure you can see that since 1952 the global influence of the US was strong in the 1950s and 1960s, but decreased in the 1970s and 1980s, stepping down once again in the 1990s and has gradually waned since the turn of the millennium. On the other hand, China, which had little global research influence at all until the 1980s has grown significantly in the last three decades, overtaking the UK in the last few years.

However, what is striking about Figure 1 is that the Commonwealth has not only established a solid foundation of global research influence (doubtless due to its large “surface area”, with 56 countries collaborating globally), but that it has also begun growing significantly in its influence in the last 20 years. Of course, when the Queen originally became the Head of the Commonwealth, there were just 8 member states and hence their influence would have been even less than shown in the diagrams here. Our analysis follows the influence of the full current 56 member states throughout the life of the Queen’s reign. While the influence of this group may be unsurprising as it counts highly developed research economies such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand amongst its number, it should also be recognised that it is a disparate collection of countries that includes small and developing economies as well as large ones.

The spread of internet technologies (as mentioned above, an innovation that owes an important part of its lineage to the UK) has enabled smaller nations to play on the international stage of research – a distinct advantage for some Commonwealth-member countries who share a common set of values, language, and a legal system, that all facilitate collaboration. In the age of the internet, distance is no longer a barrier to these countries working together on research projects Hence, while the UK (separate from the Commonwealth) has generally waned in its international research influence, it is notable that it has been less susceptible than others such as the US and the EU to decline in influence. We suggest that this is likely to be due to its strong ties with Commonwealth nations.

Over the modern Elizabethan era, the world has moved from an age of physical empires through the space race and the computer revolution to an age of information and virtual empires. From a political perspective, the UK relinquished its role as global power and instead needed to content itself with the role of influencer on the world stage. In an elegant parallel, the monarchy moved from being a “great Imperial family” to influencers both culturally and politically. The Queen’s personal style transcended the geopolitical zeitgeist as she lent her personal brand to long-term projects such as the Commonwealth.

By all accounts the Queen believed in the Commonwealth as a group of nations who could make positive change and she fought for that. In the case of research, as the US and EU gradually wane in their influence, it may well be that the Commonwealth has the collaborative spirit, as well as the geographical and cultural diversity to continue to influence the world positively. If true, this would be a worthy legacy for someone whose life was one of service.

About Dimensions

Part of Digital Science, Dimensions is a modern, innovative, linked research data infrastructure and tool, re-imagining discovery and access to research: grants, publications, citations, clinical trials, patents and policy documents in one place. www.dimensions.ai

About the Authors

Daniel Hook, CEO | Digital Science

Daniel Hook is CEO of Digital Science, co-founder of Symplectic, a research information management provider, and of the Research on Research Institute (RoRI). A theoretical physicist by training, he continues to do research in his spare time, with visiting positions at Imperial College London and Washington University in St Louis.

Simon Porter, Director Innovation | Digital Science

Simon Porter has forged a career transforming university practices in how data about research is used, both from administrative and eResearch perspectives. As well as making key contributions to research information visualization, he is well known for his advocacy of Research Profiling Systems and their capability to create new opportunities for researchers.