The Secret (Research) Life of the London Underground

London’s Underground system was built on the back of the first industrial revolution – a key piece of physical infrastructure that led to a whole new way of thinking about transportation and which fundamentally changed the city in which it was built. It is easy to see parallels between the physical infrastructure building of the 19th century and the cyber infrastructures that we are building today, as the exponential industrial revolution, powered by computers, the internet and AI in which we currently sit develops. Much has been written about cyber infrastructures – there are over 5.7 million publications classified as “Information and Computing Sciences” (of which 3.1 million relate to AI and Image Processing) in Dimensions at the time of writing. While good infrastructure is often invisible, in the sense that it merges seamlessly into and becomes part of our lives, it is, perhaps, surprising to know that the London Underground also lays claims to a significant body of research.

Today marks the launch of London’s newest and shiniest piece of transport infrastructure – the Elizabeth line, which connects the far west of London, including Heathrow Airport (and ultimately out beyond Reading), to its eastern environs in Stratford and Abbey Wood. For those of us who are frequent travellers (or, more accurately, who used to be frequent travellers before COVID and issues of sustainability reigned us in) it is heartening, finally, to see a high-speed transport link that runs across London. In honour of the Elizabeth Line’s launch, we thought that we would do a little digging into the London Underground on the Dimensions platform where we uncovered a huge range of impacts across a wide range of topics.

Beyond the 42km of new tunnels and the new stations with their clean lines, this new line shows that London as a city continues to expand, extend and change in a variety of different ways. The London Underground, or Tube, is an iconic part of London and holds a special place in the hearts of many Londoners. There is a sense of pride in the design principles behind its maps and iconography, and the fact that it is the oldest such mass transit system in the world, which first opened in 1863. That pride will only increase now that we can understand a little more about its rich research history.

In recent years, the London Underground has moved beyond merely being a transport system and is now the subject of many books, from Stephen Smith’s excellent Underground London: Travels Beneath the City Streets to Andrew Martin’s intriguing Seats of London: A Field Guide to London Transport Moquette Patterns. It is not, however, only authors of books who have taken an interest in the Tube – there is a surprising amount of research material that makes reference to the London Underground and, in commemoration of today’s launch, we thought that we would give some insight into the way in which the most recognisable transport system in the world has been referred to in the research literature.

We specified a general search term as a high-level ‘catch all’ in Dimensions:

As of 24th May 2022, this search string returns just over 90,000 publications, 66 datasets, 104 grants, almost 25,000 patents, 4000 policy documents and 3 clinical trials. At first glance, this wealth of output is astounding and unexpected. Indeed, barely a year goes by when between 3000 and 4000 publications (equivalent to the research volume of a fairly sizeable university) don’t mention the London Underground in some form. But, when you think about the ways in which such a historic transport system touches different aspects of our lives you begin to understand why it is mentioned so much.

Walking the landscape

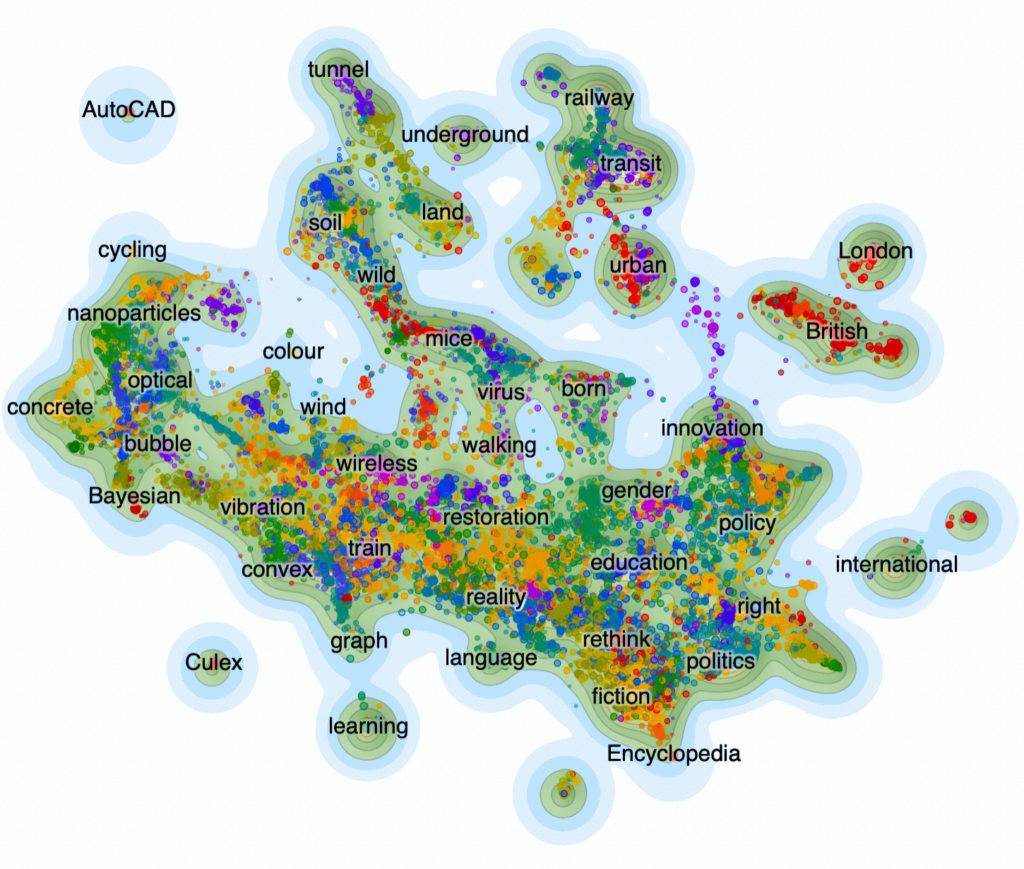

We mentioned the importance of the London Underground’s maps and iconography, so it’s only natural we should make our own map of the landscape of London Underground research. Figure 1 is a high-level topic map of some of the more recent work that mentions the London Underground using Lingo4G. The closer areas are, the more closely connected they are; words that are shown are derived from article titles; colouring indicates groupings (note that some colours are repeated so that, for example, blue in one area of the graph is not necessarily the same topic group as another area of the graph). Just looking at this high-level representation gives an impression of the immense diversity of topics covered in the literature.

Just to give a flavour, topics range from: Accessibility (of the Tube map) to station accessibility for disabled people; urban design and congestion analysis; use of solar cells and graphene in mass transport systems for sustainability; economics and public policy (private-public sector partnerships); film and fiction (as a venue for movie making or as a setting for narrative); fuzzy logic and control systems (in train service optimisation); history (relationship to the industrial revolution); crisis management and terrorism (relationship to threats in public systems); epidemiology (virus spreading on the Tube and the prevalence of Culex Mosquitos on the Tube network as disease vectors); human interface design (the Tube map); network theory (as a commonly recognisable analog for the mathematical concept of a graph); climate change (how mass transit can be a powerful weapon against climate change); cybersecurity (protection of infrastructures against attack); geology (tunnelling through challenging formations); and crime (policing unusual environments).

This list merely scratches the surface of the rich research topics that surround the London Underground. One hundred and fifty nine years into the existence of this key piece of infrastructure, its cultural, historical and research impact is not at first evident.

Distinctive personalities

Of course, while the London Underground was the first major subterranean railway, it is not the only one. Many, including Shanghai, Tokyo, Paris, Singapore and Berlin are busier. Despite the unique and beautiful tiling designs across the London Underground, Moscow’s Soviet-inspired mosaics and Paris’s Art deco might be considered to be more aesthetic. London is only 10th in the world in length of track and 9th in number of stations. However, arguably it has had the most research articles written about it, with the New York Metro coming in a close second at 86,000 outputs, and other notable mentions being the Paris Metro with more than 14,000 outputs and the Tokyo Metro with almost 13,000 outputs.

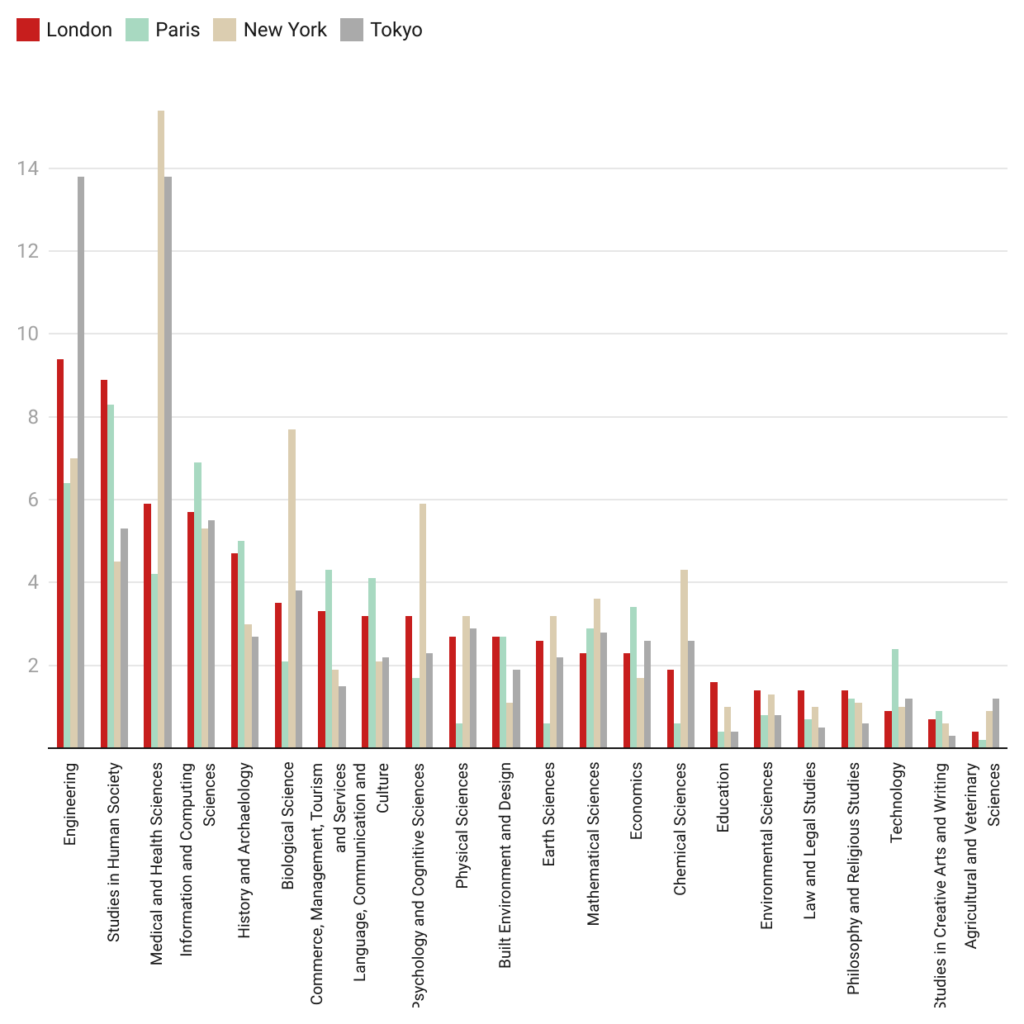

Each of these systems has its own personality and, again, looking into Dimensions and, comparing the different queries on a subject level by ANZSRC FOR code at the 2-digit level, we can see a little of those personalities emerging in Figure 2.

While the London Underground is most studied from the perspective of Engineering and Sociology (Studies in Human Society), both it and the Paris Metro are not nearly so studied (relative to overall output) as the New York Subway and Tokyo Metro for Medical and Health Sciences. Engineering is not such a strong theme for New York and Paris (presumably because much of the network is much nearer the surface and less tunnelled than either London or Tokyo). London and Paris share a peak in History and Archeology for understandable reasons.

It is, perhaps, also interesting to note the “inner life” of these underground reflections of the cities above. Again, relative to the overall output of research New York has a significant peak where researchers have written about Psychological and Cognitive Science topics whereas the London Underground has been more discussed in the Education literature. The Paris Metro has had more attention in works on Economics and in Creative Arts and Writing.

International Attention

The final musing that we want to leave you with is that despite the local nature of transport systems, they attract international research attention. Indeed, 87.7% of the research outputs relating to the London Underground do not feature a UK-based author (although of that 12.3% focus from the UK a very considerable number of papers (more than 3000) can be attributed to London-based institutions). It is a similar story with other international transit systems – Paris enjoys a similar percentage of international attention to London with New York and Tokyo both being a little more locally biased with 77.3% and 80.9% of their research coming from non-local sources.

While research on underground railways in general has been the focus of this piece, a cursory look at both scientometric and bibliometric research literature suggests that understanding the scholarly record around London Underground has not been a priority for the community. But, with the launch of the Elizabeth line today, we are confident that this is about to change! We hope that this brief analysis demonstrates that there is so much more to the Tube than getting from A to B and inspires you to search Dimensions for your favourite topics.