Subscribe to our newsletter

Rockin’ In The PID World At PIDapalooza

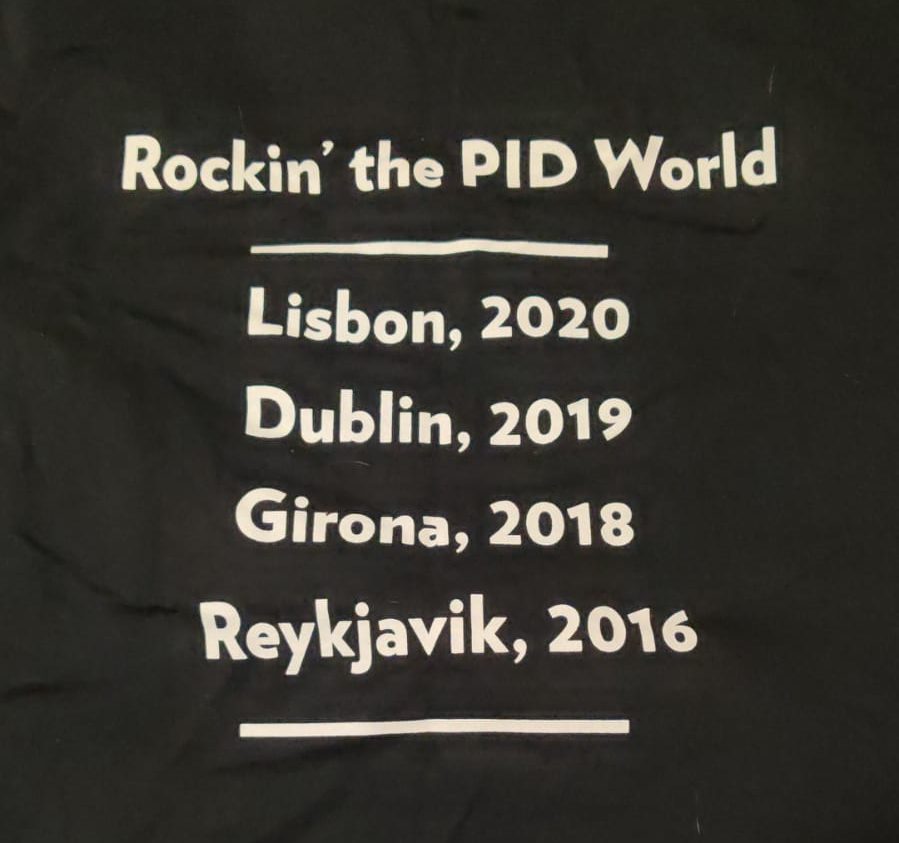

The last week of January 2021 saw the annual PIDapalooza festival of persistent identifiers go virtual. Armed with a ‘tour shirt’ that boasts such epic previous host cities as Reykjavik, Lisbon and Dublin, my cafetière of coffee and I settled in for a 24-hour bonanza of all things PID.

After a warm welcome from the organisers and the traditional lighting of the eternal flame (“surely if it is eternal it is already alight,” I hear you say – and it is, in our hearts. But it needs plugging in for the festival…) the delegates got down to business. Just over 24 hours worth of identifier-related treats had been packed into concurrent streams, with many sessions taking place in languages local to the least sleepy time zone at any given point in the programme, adding to the inclusive nature of the conference. But what is PIDapalooza all about?

Where there are data, there are persistent identifiers. Whether that data is related to research information, or whether it is related to other items that need classification, categorisation or organisation, persistent identifiers are a form of metadata that allow us to better understand the context of a single piece of information.

Think about it in the context of your favourite music library. When you import your music, each individual file is organised by track number and album. There is however a whole raft of additional metadata that you may not be aware of. These additional layers of detail allow you to collate your songs in different ways. Let’s say I wanted to kitchen-disco dance to the songs that soundtracked my undergraduate years. All I need to do is search my music by the year 2005, and my library will return all the songs I own that were released then. Perhaps I’m in the mood for some epic prog-rock to power me through these long pandemic days. No problem, as the genre tag will do the hard work for me. All this is possible thanks to rich and accurate metadata; the information that describes a file with fine details that add context.

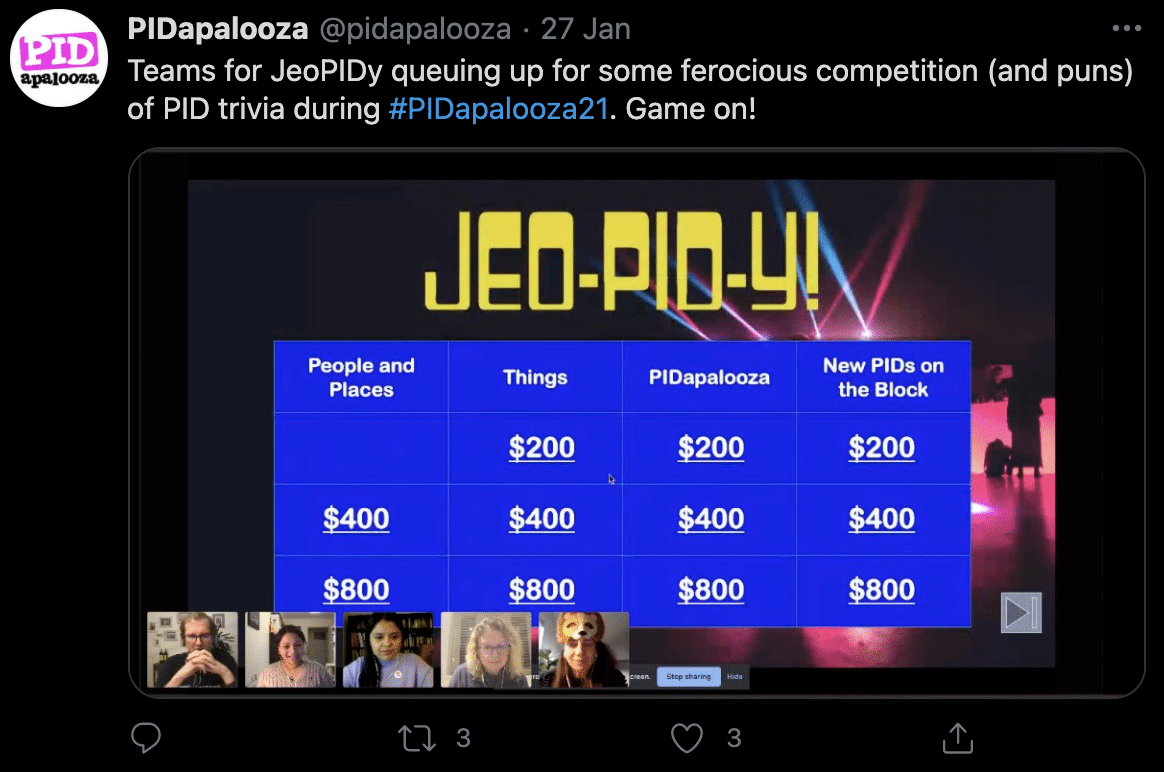

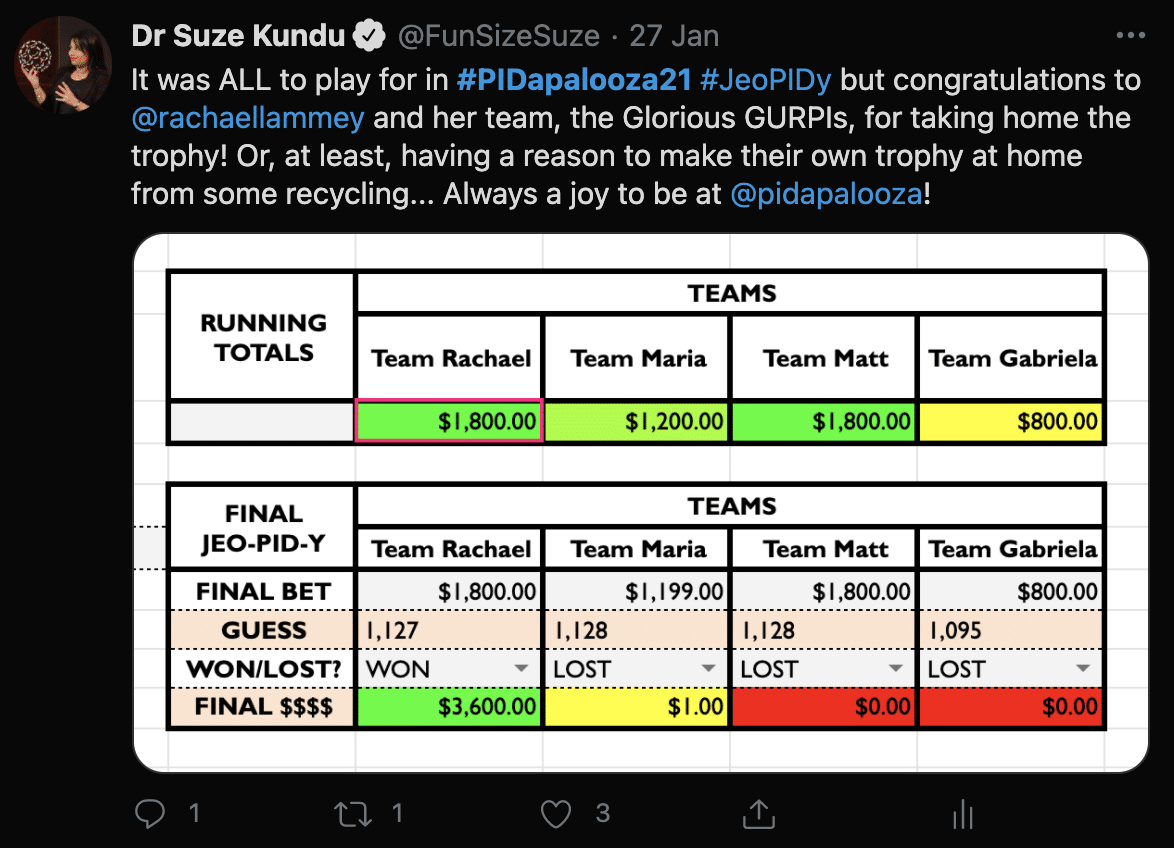

PIDapalooza is a conference unlike any other. From the aforementioned tour t-shirts, to the PIDaparty sessions, the conference allows people to naturally network, communicate and collaborate, and interact with speakers and other delegates. This year I hosted a frantic session of Jeo-PID-y, a game show all about PIDs based on the US show with a very similar name. Devised by Alice Meadows of NISO, Helena Cousijn of DataCite and myself, the game was an opportunity to test your PID knowledge, meet others via hosting platform Crowdcast and in Slack, and learn about some ‘new PIDs on the block’ (I’m not even sorry). Thanks to a combination of enthusiastic participants and four excellent team captains in the form of Maria Gould from ROR, Matt Buys from DataCite, Gabriela Mejias from ORCiD, and Rachael Lammey from CrossRef, the game was educational and entertaining. Rachael’s team, the Glorious GUPRIs, took the crown after some strategic betting of entirely fictional money in Final Jeopardy.

PIDapalooza brings together users of persistent identifiers from a range of different professions, each facing similar challenges, all sharing best practice and novel ways to overcome these hurdles. This year’s programme featured a session led by Jonathan Clark from The DOI Foundation and Raymond Drewry from MovieLabs and the Entertainment Identifier Registry, or EIDR. They shared the successes and challenges of creating and maintaining PIDs for the entertainment industry. Complete with movie quiz, the duo answered questions about how to attach unique identifiers to different versions of movies, such as director’s cuts and extended editions, and how to categorise movies in different languages. When we think about research information, it is clear to see the parallels between the challenges that other industries face and those we encounter within research. One message shone through multiple sessions, however; the better the metadata, the more we can do with that incredible depth of information.

At Digital Science, we have overcome our own PID-related challenges and continue to work with our community to best integrate PIDs in our work. When creating the Dimensions database, the team needed a disambiguated research organisation identifier in order to categorise research outputs by institution. Enter GRID, the Global Research Identifier Database. This free-to-use identifier adds another layer of metadata to your research outputs, and can also be incorporated into new systems. As part of the curation process, GRID brings together other persistent identifiers, and even adds more richness to the metadata available about each institute by including geographic location, NUTS3 region codes, and much more for greater analytical potential of research information.

GRID is used in Altmetric, Dimensions, Figshare, and Symplectic Elements, but its reach doesn’t stop there. Where there is PIDapalooza, there is a pride of ‘ROR-ing’ lions close by. GRID seed data was used to help build the Research Organization Registry, or ROR. ROR’s first annual community meeting took place in Dublin just before PIDapalooza in January 2019. As one of the newest PIDs, it made sense for a stakeholder-governed identifier community to meet around PIDapalooza, as the same people would attend both events. The ROR community meeting allowed users and future adopters to learn more about how the ROR project is progressing, and what the next steps are. Being driven by the community, it was another great opportunity to hear about new use cases and learn about the priorities of different users in between the quarterly community calls.

Though ROR and GRID are well known within the PID community, it is easy to forget that researchers may not know much about them. Just over two years ago, fresh out of academia, I had to Google what a PID was when I joined Digital Science and started working with the ROR project team. Little did I know that everything, from the names I assigned to my individual experiments to the digital object identifiers (DOIs) attached to papers, were forms of persistent identifier. As Kathryn Kaiser said in her excellent wrap-up, perhaps researchers don’t need to know the ins and outs of the infrastructure of research information. They just need to know that good metadata means that the rest of the research world can make better connections between pieces of research information, and we need to continue to understand our research community in order to know how best to support them in adopting these.

The eternal flame may have been unplugged for another year, but I already look forward to reconvening with this community in January 2022 to celebrate the progress that has been made and share what we have learned along the way.